ILLUSTRATION BY MICHAEL SHIREY

Dublin-born author Brendan Behan once quipped he was “a drinker with a writing problem.” If he were alive today — he died in 1964 at age 41 from diabetes complications brought on by massive alcohol abuse — he might also admit to a serious public image problem.

In the eyes of the Irish, Behan sits, albeit uneasily, alongside their greatest authors — Samuel Beckett, James Joyce, Bram Stoker, Oscar Wilde, George Bernard Shaw, and Frank McCourt, to name a few. His work, infused with raw, authentic language, broke new ground in articulating the plight of the working class. Two of his plays, “Quare Fellow” and “The Hostage,” were ardently received in New York. His autobiographical novel “Borstal Boy” was a worldwide bestseller, later turned into a critically praised film.

Yet for some reason, the literary bad boy, once a member of the Irish Republican Army, has failed to fully register in America. It’s especially mystifying, given that Behan spent a decent chunk of time living in New York, the place where the malcontent was said to be at his happiest.

The soused, subversive Irish writer New York should know

And now “Brendan at the Chelsea,” a play based on the memoir “Brendan Behan’s New York,” aims to do some long overdue damage control. The five-character drama, written by his niece Janet Behan and directed by the veteran Irish actor Adrian Dunbar (who also plays the title role), was a sensation at the Lyric Theatre in Belfast and has now landed at New York’s Acorn Theatre Off Broadway.

“It’s always been our ambition to bring Behan to New York,” Dunbar said of the play, which centers on the writer’s last night in the Chelsea Hotel before he returns to Dublin, only to die four months later. “It’s a very New York-centric play; however, we don’t know how audiences will respond. He is not a household name. We’re taking a huge risk. It feels like a Brendan Behan play, brutally funny and insightful.”

As Dunbar sees it, Behan lacks an organized constituency, coming from the Dublin working class and with no university pedigree. “He was garrulous, alcoholic, angry, excommunicated, and bisexual if not completely gay. Yes he was married, but we’ll not go down that road. He makes a nuisance of himself and is not easy to be with. He needs people like us taking care of his memory.”

According to Dunbar, the acutely intuitive Behan was a major literary figure, especially following the hit staging of “The Hostage” on Broadway, where the boozy playwright, as the story goes, once joined the cast onstage mid-performance after drinking seven bottles of champagne.

“He legitimized the entire Beat generation,” Dunbar explained. “He was talking to Ginsberg and Kerouac, experimenting in poetry, writing in stream-of-conscious prose. It was all fueled by whiskey and bourbon, which, from what I hear, is enjoying a comeback in New York.”

Dunbar believes Behan was among the first authors to put the big issues, like political strife and capital punishment, in the mouths of ordinary people rather than the intelligentsia. “His work has a ring of sincerity and integrity about it,” Dunbar observed. “He was an excellent, groundbreaking agitprop playwright.”

“Brendan at the Chelsea” evokes a vital, exciting period in New York in the early 1960s. The dissipated iconoclast caroused in such literary haunts as McSorley's, the White Horse Tavern, and P.J. Clarke’s. He even appeared on Jack Paar’s “Tonight Show.”

At the time, the Chelsea Hotel was a hotbed of bohemia — creative geniuses like Arthur Miller and Dylan Thomas lived there. Gore Vidal, it should be noted, salaciously described a bout of furtive sex with Jack Kerouac, after rejecting the advances of William S. Burroughs, at the Chelsea in 1953. But that’s the stuff of another play.

Apparently Behan, who took to alcohol around age six, would drink anything he could get his hands on. During one bender, according to Dunbar, he got naked and ran through the Algonquin Hotel and scared the old biddies, which got him banned.

Behan’s plaque is among several other artistic notables at the Chelsea Hotel. If he were alive today, he’d be dismayed to see his beloved grungy hotel being turned into luxury condos, destined to be stripped of any funky charm.

Dunbar admits that wearing two hats — director and lead actor — is problematic, but he’s up to the challenge: “You have to concentrate on the other actors first and worry about yourself later. I have kind of a third eye watching from above. We can’t afford to employ someone else as the director, so I’ve ended up with the job.”

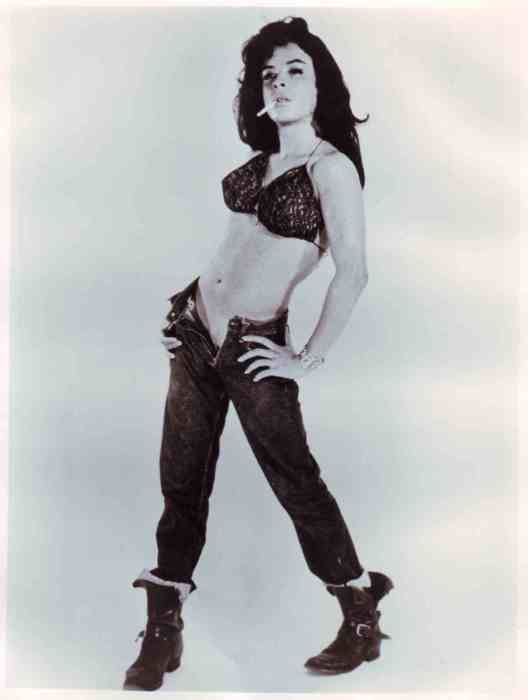

Adrian Dunbar (l.), seen in the Lyric Theatre Belfast production of Janet Behan’s “Brendan at the Chelsea.” | STEFFAN HILL

In preparing for the role, Dunbar was most concerned with perfecting the irregular speech cadences and accent. “It’s a huge canvas to work on,” he explained. “There are a lot of emotions to dredge up and it takes quite a lot out of me. But, you know, I said I could do it when I rode in.”

To anyone familiar with “Borstal Boy,” about Behan in his late teens, then a rogue member of the IRA doing time in a prison-like reform school for attempting to blow up the Liverpool docks, the Behan portrayed in the play may come as a shock.

“He’s at the end of his life and is more reflective,” Dunbar said. “Sure, once he gets a few drinks in him, he kids himself that things might get better. But In the cold light of day, he realizes he’s abused himself and his days are numbered.”

While “Brendan at the Chelsea” is rooted in fact, Janet Behan had to invent certain conversations and confrontations, especially those with his wife, Beatrice.

“He can’t write at this point because his joints are all horribly swelled up from the diabetes, so he must speak into a recorder,” explained Dunbar. “He gets these tiny flashbacks now and again of various episodes in his life.”

One of the most potent yet oddly heartwarming recollections is of a trip to Fire Island with Beatrice. Did Behan really go to the gay enclave or is that a fantasy?

“Yes, he went to Fire Island,” Dunbar confirmed. “He insisted he didn’t know what the place was all about, but I’m not buying that.”

One scene recalls them arriving at the Botel in the Pines and carousing with fun-loving boys from New York.

“It’s bizarre to look back at that time,” Dunbar said. “The idea that there would be a magical place where gay men can just hang out, have fun, and not be ridiculed or in danger — it’s quite startling. In those days you certainly didn’t shout [about homosexuality] from the rooftops.”

The director has no interest in revising the play to suit American audiences, not even softening the acerbic language (the dialogue includes variations of the expletive “fuck” some 140 times), though he is open to toning down the accents.

Somewhat gingerly, I took it upon myself to point out a minor glitch in the script, which referred to “The Pines in Cherry Grove” as if they are a single entity instead of two separate gay communities on Fire Island. Savvy New Yorkers would surely pick up on that.

“Ah, so it’s the Pines near Cherry Grove,” Dunbar said. “I believe you’ve just changed the script.”

BRENDAN AT THE CHELSEA | Acorn Theater at Theater Row, 410 W. 42nd St. | Sep. 4-Oct. 8; Tue. at 7 p.m.; Wed.-Sat. at 8 p.m.; Sat. at 2 p.m.; Sun. at 3 p.m. | $55.75 at BrendanChelsea.com or 212-239-6200