The Global North often imagines — and continues to position — the Caribbean as an ongoing site of queer death, violence, and impossibility. Legacies of colonial buggery laws, ongoing and escalating rates of queer and trans hate crimes, and nationalist politics within the region that privilege the cisgender heterosexual as always the ideal citizen work to position gender and sexual difference as always marginal and outside the space of Caribbeanness.

In addition, myriad articles and Western news outlets work to amplify narratives and mythologies that Caribbean nations — specifically, countries such as Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, and the Bahamas — are “the most homophobic places on Earth” and often need to be “saved” through the lessons of the “free” queers of the North to achieve queer modernity.

These messages of homohegemony are further exacerbated by popular queer media and cultural productions, such as “RuPaul’s Drag Race” “and “Gaycation,” that suggest “legitimate,” “authentic,” and “valid” forms of queer life are only to be found within the “safe havens” of diaspora. From this perspective, places such as the US, Canada, and Europe offer landscapes of freedom, liberation, and safety. Thus, Caribbeanness and queerness become incompatible.

Resilience, resistance, and transgression in the Caribbean and the Caribbean diaspora

For instance, in a recent 2020 episode of “Canada’s Drag Race,” contestant Anastarzia Anaquway, a Bahamian-Canadian drag queen, shared a moment that amplified these imaginings of queer Caribbean life. She explained that while living in the Bahamas, she was shot in a homophobic attack and almost died. During this segment, she went on to sing the praises of Canada, explaining that the process of seeking asylum was quite easy for her, providing her with space to live queerly without threat of violence.

Caribbean drag artists on “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” such as Vivacious (Jamaican-American), Priyanka (Guyanese-Canadian), and Monét X Change (St. Lucian-American), have also shared stories involving serious violence faced by queer and trans people in the Caribbean.

Although acts of homo- and transphobia are rampant in the Caribbean, such narratives forget to account for the ways in which queer and trans Caribbean communities have made space to pursue their same-sex desires and pleasures and organize against and resist heteropatriarchies. Such stories, however, are often elided on these programs where, instead, a homonationalist politics involving belonging and even becoming citizens in the US or Canada is celebrated. This simultaneously works to suggest for one to attain a queer Caribbean life, one must either adhere and veil their queerness through performing heterosexuality or ultimately articulate one’s sexual or gender diversity and risk social exclusion, violence, and possible death.

As many queer and trans Caribbean communities know and experience, however, the Global North is far from a space of liberation and freedom for Black, Indigenous, and other people of color. Mainstream queer spaces, programming, and services often work through frameworks that privilege the histories, challenges, and narratives of white, cisgender, LGBTQI+ communities that often bifurcate the complexities of race, gender, class, ability, religion, and other vectors of experience that shape queer and trans Caribbean lives. For this reason, Caribbean-centric organizations such as Barbados Gay and Lesbians Against Discrimination (BGLAD), the Jamaican Forum for Lesbians, All-Sexuals and Gays (JFLAG), the Society Against Sexual Orientation Discrimination (SASOD) in Guyana, the Coalition Advocating for Inclusion of Sexual Orientation (CAISO) in Trinidad and Tobago, the Black Coalition for AIDS Prevention in Toronto, and the Caribbean Equality Project in New York have emerged. Engaging in critical and much-needed work to provide support and resources for the specific complexities of queer and trans Caribbean life, these organizations respond to gender-based violence, hate-crimes, mental health, social exclusion, housing, and legal challenges that specifically affect Caribbean communities.

Such community groups provide clear evidence that despite the mythology that “legible” and “valid” forms of authentic queer life can only exist in the North, the Caribbean has always been a site of gender and sexual transgression, community, and organizing. Furthermore, if we turn to local festive celebrations in the Caribbean such as Carnival, Jab Jab, the Matikor/ Dig Dutty, Phagwah, Londa Ke Naach, and other rituals, we can see how cross-dressing, genderplay, inversion, and role reversal have always been deeply embedded into the cultural fabric and landscape of the region, providing Caribbean queers with methods to remix, resist, push back and mash up Western, neo-colonial ideas of “authentic” sexual and gender practice.

In places like the rum shop, the beach, the fête, queer pageants, the nightclub, the dancehall, the market, and other spectacular and mundane places of congregating and celebrating pleasure and joy, queer and trans Caribbean folks have worked to transgress, challenge, and critique the rules of normalcy. Here, the body becomes the medium to “free up” or transgress the limits of heteronormative living and being. With this in mind, the Caribbean has been and will continue to always be a place of queerness.

Defying the norms of the Global North, of dominant Euro-American Pride and activist organizations, and of mainstream queer media, Caribbean ways of doing queerness have never neatly fit within the rules of Western queerness. In particular, the work of Caribbean drag artists have led the charge on what it means to undo the normative scripts of gender and sexuality. Drawing upon histories of resilience, freedom-seeking, transgression, and community-building, Caribbean drag artists use popular culture to reconfigure queer living through the lessons passed down to us from ancestral teachers. Moving through histories of slavery, indenture, and indigenous genocide, queer Caribbean communities have created places for one another and enacted their own non-normative pleasures and desires through traditions of transgressive celebration, joy, pleasure, and desire — most notably, music, dance, comedy, and story-telling.

Using the “mash-up” as method, Caribbean drag critiques the notion that queerness and Caribbeanness cannot exist simultaneously. Instead, whether located in the region or in diaspora, these artists use their bodies to articulate forms of sexual diversity that speak a language all of their own — refusing the the queer mainstream’s hegemonic vernacular.

Long-standing legacies based in distinct forms of Caribbean gender performance have moved through queens, kings, and other queer and trans artists such as Angelique Ali, Karma Sutra, and Sarah Marsala in New York, Michelle Ross, Devine Darlin, Jada Hudson, and Tynomi Banks in Toronto, and Mizz Jinnay in Trinidad and Tobago, among others. Distinct spaces of Caribbean drag like the Gay Caribbean USA Pageant have created affirming and transformative celebrations of drag and Caribbean culture in Brooklyn.

According to Mohamed Q. Amin, the founder and and executive director of the Caribbean Equality Project, “Founded by Marlon Gervis in 2009, the inauguration of the pageant gained Caribbean media attention, which fueled needed and meaningful discussions on the acceptance and dynamics of queer Caribbean identities in the diaspora. The pageant created an inclusive opportunity for Afro and Indo-Caribbean drag queens and trans women to showcase their work while speaking out against homophobia and anti-LGBTQ hate violence in the Caribbean. Some of the notable contestants included Monét X Change, who competed as Miss Saint Lucia and was pronounced winner of the 2014 Gay Caribbean USA Pageant.”

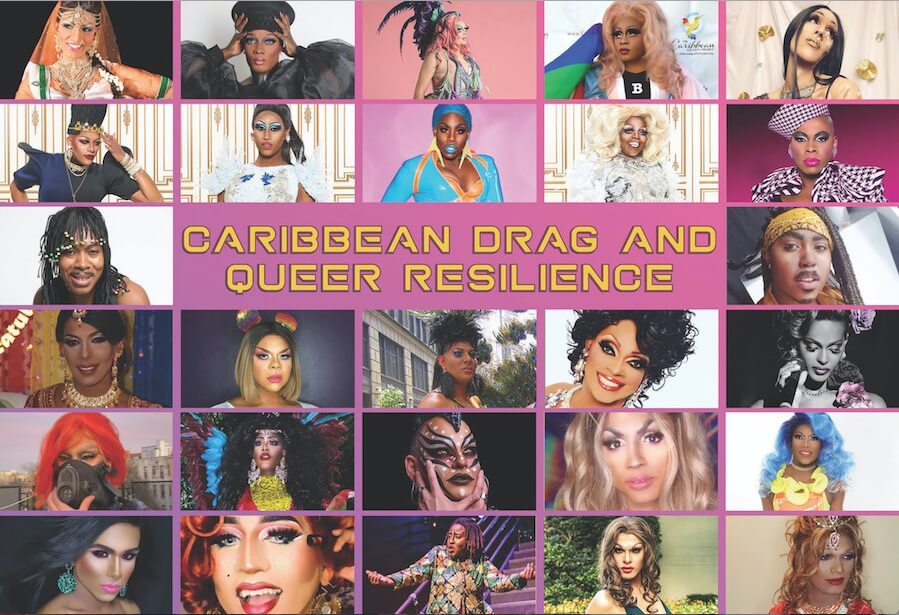

Emerging out of these legacies, contemporary Caribbean drag artists remind us what it means to cultivate embodied languages to speak our distinct histories and contemporary positions as well as to mount resistance and rehearse futures of anti-oppressive worlds to come. Eighteen Caribbean drag queens from across the US, Canada, and the Caribbean region speak here about what coalition and liberation work means to them.

Jahlisa A. Ross (@jahlove_thebrand)

Garifuna-American

Staten Island

“[I am a] show-stopping dancing diva. In my culture, we express ourselves through movement, and I have adapted that into my drag art. My liberation happens every time I perform in drag because I feel free. I have infused the love I have for entertainment with HIV advocacy into my art.”

DJ Nina Flowers (@djninaflowers)

Puerto Rican

Denver

“[Nina Flowers] is androgynous, mysterious, edgy, sensual, and fun. The world is experiencing some drastic changes due to our current and devastating situation. Artistically, and I speak from personal experience, we have been forced to put our careers on hold and wait until the pandemic is over. There’s not much room for anything else. It’s been like a never-ending nightmare. I’m sure most of our fellow artists feel the same.”

Phil Atioh (@phil_atioh)

Afro-Jamaican-Canadian

Toronto

“Phil expresses his Caribbean identity through his diverse song choices and, of course, his waistline. When his hips are moving, there isn’t a doubt that the rhythm didn’t come from spending days and nights bumping to dancehall and soca. Many people can agree that several Black styles of music have influenced most music (and currently, most pop music). Dancehall and reggae are no exceptions. So when I can see that many of these artists take time to use their reach to spread knowledge and understanding about specific topics, it gives me hope. Jamaican artists especially are always quick to release music related to current politics and worldwide events. For example, many performers released songs outlining the 2008 election for the first black president, and even now are creating songs that spread the awareness of COVID-19.”

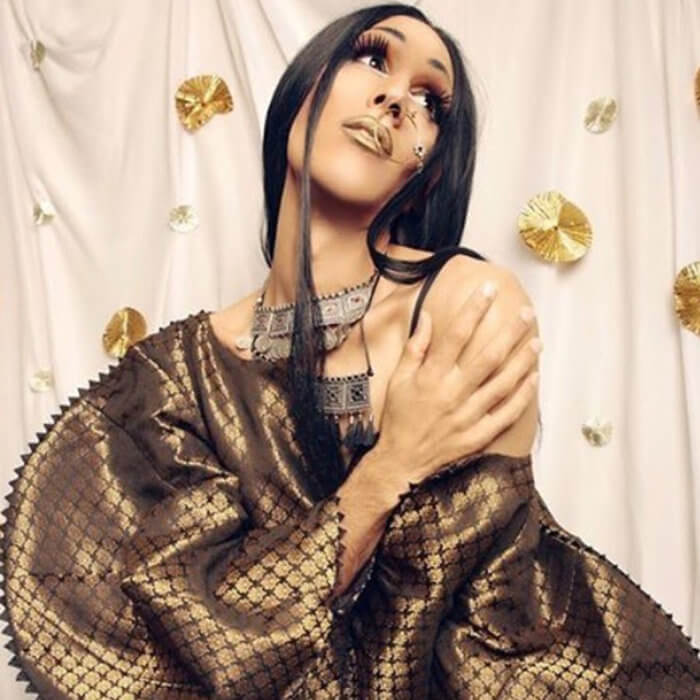

Sundari, The Indian Goddess (@zaman_aka_sundari)

Indo-Guyanese

Queens

“In 2012, Sundari was cast as a female dancer in a non-LGBTQ cultural dance drama titled ‘Kitcheri’ in Queens. The birth of Sundari and performing arts spaces helped me to create opportunities for other drag identities and LGBTQ+ visibility in traditional heteronormative and faith-based institutions. Indo-Caribbeans have a long history of LGBTQ narratives in our culture, religion, and traditions, which have been erased and became unacceptable in society due to homophobia and colonialism. I find liberation in pushing boundaries in non-LGBTQ spaces with the work I’m doing in and out of drag.”

Bijuriya (@bijuriya.drag)

Indo-Trinidadian/ Mixed-Race

Montreal

“I draw lots of inspiration from Desi culture and seek to portray different contrasting versions of brown femininity, from Bollywood heroines to M.I.A. I often feel suspended between identities, so my drag tends to hover between tribute and parody, or appreciation and critique of the culture(s) I engage with. I love to engage with very specific, sometimes relatively obscure cultural references in my drag because I DON’T think that art is universal. Thinking of art as something that has the potential to please everyone on the planet is an insult to all the subcultures that thrive unbeknownst to the dominant culture. I want to challenge the hegemony of mainstream culture whenever I can, but being a polite yet witty Canadian it never comes across as aggressive, more so like an invitation to reflect. When performing to a Bollywood or Caribbean song in a Montreal event or online, I hope it can either empower that brown person that feels outnumbered in the room or serve as a reminder that there’s so much culture in this world that we simply do not know about. Ignorance is absolutely normal, acknowledging our own ignorance is a step toward equal to equal dialogue, where all parties accept that they have something to learn.

Michelle Ross

Afro-Caribbean

Toronto

Detoxx Bústi-ae (@detoxxbusti_ae)

Afro-Jamaican

Brooklyn

“I consider my drag persona to be a melting pot of spices, a blend between the Pussycat Dolls and Beyonce with a voice for the community. When in drag, I often draw inspiration from my Jamaican culture and colors for my many different custom costume creations. I am able to use my voice and platform as a drag entertainer to enrich the community by standing up and speaking out against the many injustices people like myself face day to day as a queer Caribbean-born immigrant living in America.”

Sheila, De Dancin’ Diva (@sheila_d_dancingdiva)

Indo-Trinidadian

Trinidad and Tobago

“Sheila is more than an alter ego; she is a form of expression and art. Sheila is an all-out classy, sophisticated diva who specializes in dance entertainment, makeup artistry, and LGBT activism. She stays true to her rich Indo-Caribbean heritage and background through her stage name, her music/ dance techniques and selections, and her attire. The confrontational art of drag has often been visible on the front lines of Caribbean LGBT activism. That tradition continues today, and performing publicly as a drag entertainer on national stages in predominantly heterosexual spaces in itself makes each performance a unique form of activism for the LGBT community, creating a space for us in all facets. So I will say each of my performances is a campaign for liberation, freedom, equality, and visibility.”

Stefon Royce (@stefonroyce)

Afro-Boricua/ Puerto Rican

Queens

“I express my Caribbean identity through Salsa music and dancing Salsa. Bomba dancing and music, as well. I make it known I am Puerto Rican in performance by costumes with the Puerto Rican flag and colors. I even lip sync in Spanish. I see the work I am doing as a Caribbean artist as committed to the community and being a role model to many. I am a motivational speaker, as well as a Caribbean drag artist. I seek to reach out to the youth and those identifying their truth. I help them express that through my story, so it motivates them to become who they truly are meant to be.”

Kimora Amour (@amour_kimora)

Dougla/ Mixed-Race

Scarborough, Ontario

“Kimora is known for elaborate stoned and feather garments. While getting her start in the Kiki Ballroom, she is now a fully imagined pageant queen. I feel Caribbean artists, especially Indo-Caribbeans, have to ensure to not only admit that racism does exist in the Caribbean and throughout the diaspora, but also wholeheartedly denounce it and work toward actually unifying the races. Being a biracial Caribbean queen, I get to take part in more conversations from a different point of view, as well as use performance to tell stories that some are unable to emote through the art of lip-syncing properly.”

Curry Anne Durr (@currytingz)

Indo-Trinidadian-American

Fort Lauderdale

“I’m an advocate first and foremost. I started to do drag for my brother, who passed away from AIDS, after I was asked to walk a benefit runway. I never looked back. Drag is and will always be a protest for me. I want to represent what I would’ve liked to see growing up. I want another little brown gay artist to express their nature through their art and not feel withheld or trapped in an old-world mentality. Let them feel like there’s something fun to smile about too. ‘Cause drag is political, funny, artistic, and deep at times.”

Devine Darlin (@devinedarli)

Afro-Jamaican

Toronto

“Being a Caribbean drag queen is one of the hardest and toughest things for me to do. Simply because in the Caribbean, it’s frowned upon being gay and a drag queen. In today’s drag culture, an Afro-Caribbean drag queen has to work twice as hard. We have to put in that extra work because that much is expected of us. It’s one of the hardest things to do, to keep that sustainability of having a face in the community or showcasing your talent, and it comes with a lot of hardship.”

Tifa Wine (@tifa.wine)

Indo-Trinidadian/ Mixed Race

Toronto

“I work through legacies, energies, and histories of Indo-Caribbean feminisms to articulate my queer, diasporic position. In particular, I am largely drawn to the figure of tanties and mausis (Afro- and Indo-Caribbean aunties) who, for generations, have used sound, dance, and their own bodies to imagine, enact, and rehearse what it means to free up one’s self and work to dismantle systemic oppression.”

Buster Highman (@thebusterhighman)

Afro-Jamaican

Toronto

“Being a Caribbean drag king runs deep because now I’m able to show the world something that I’ve not really seen. It’s such a beautiful thing that I have the opportunity to share a bit of my culture through the music and the dance moves that I use.”

Karma Sutra (@queen.karma.sutra)

Indo-Trinidadian

South Florida

“Caribbean drag artists, now more than ever, must use their art to come together to inspire and unite against the global division of races as most of us recognize that the Caribbean is a melting pot of culture. It’s the unique blend of people that make us and our beautiful islands so special!”

Laila Gulabi (@lailagulabi)

Indo-Guyanese/ Mixed-Race

New York City

“Laila has never been vanilla — with Laila, I draw from various aspects of my mixed heritage through music, dress, and jewelry. Performing as Laila has helped me grow my understanding and navigate being Indo-Caribbean in predominantly white settings. I like to think of my drag as invoking the thought of celebrating and honoring my ancestors, who traveled across the seas to Guyana. My drag disturbs notions of patriarchy, masculinity, gender, and sexuality with colonial, hegemonic origins in Caribbean communities. Buss’ing down a fine whine can be very impactful just like yuh naani an’ auntie dem. My drag is liberation and resistance to the various manifestations of colonial and post-colonial violence and trauma, and I hope it paves the way for more folx to find themselves and their voices, however that manifests.”

The King Ivy (@thekingivy_)

Cuban, Puerto Rican, Guyanese

Brooklyn

“I’ve always been happy to represent my culture in order to inspire others to be fearless and free-spirited. Growing up in a Latin household, it was challenging to be gay. I had to talk, act, and dress a certain way. I was always scrutinized to do better. So for me, drag is what gave me back my voice to speak and say this is my life, and this is who I am. It was my drag point of view that helped me reach a higher power in hopes of inspiring other Latin Caribbean queens to be different and do whatever makes them happy.

Maria Venus Raj (@thevenusraj)

Indo-Trinidadian

Trinidad and Tobago

“In Trinidadian politics, it’s sad that LGBTQ rights are still characterized as taboo. Two years after the buggery law was challenged, hate, ridicule, and discrimination are still prevalent in society. Being able to liberate myself and inspire a lot of people to live their true life [is important]. When I’m on stage, performing or doing a photoshoot, there is nothing but joy, confidence, and happiness that exudes in me. Unfortunately, it’s something I can’t do full-time in Trinidad because of the negative view of the public and the consequences that come along with it.”

This project was curated by Ryan Persadie and Mohamed Q. Amin of the Caribbean Equality Project. Persadie is an educator, drag artist, and PhD candidate in Women and Gender studies at the University of Toronto. His doctoral research investigates queer Indo-Caribbean diasporas and the ways in which performance, and specifically music and dance, offer salient queer archives for descendants of indenture to negotiate as well as disrupt normative notions of sexual citizenship, belonging, queer identity, and “Pride” in Toronto and New York City. To learn more about the Caribbean Equality Project, connect on YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram at @CaribbeanEqualityProject and on Twitter @CaribEquality.

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter.