ILLUSTRATION BY MICHAEL SHIREY

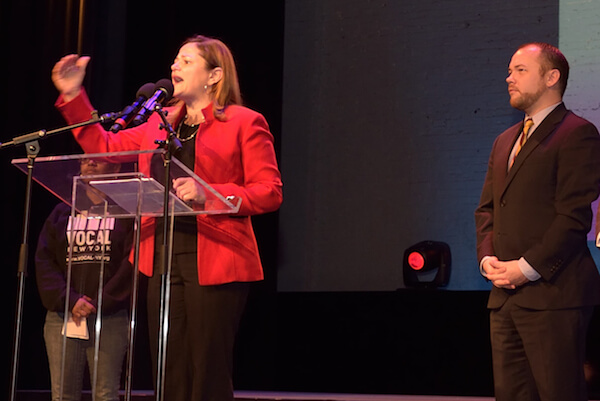

At a World AIDS day event held at Harlem’s Apollo Theater, Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, the assistant commissioner in the city’s health department who oversees HIV programs, made a bold promise.

“I am tired of hearing that that New York City is the epicenter of HIV,” Daskalakis told the crowd at the December 1 event. “New York City is going to be the epicenter of the end of HIV.”

In June, Governor Andrew Cuomo endorsed an ambitious plan sought by AIDS groups that will use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), among other interventions, to prevent new HIV infections and to use treatment as prevention (TasP) in HIV-positive New Yorkers so that they are no longer infectious. Under the plan, new annual infections in the state would fall from roughly 3,000 currently to 750 by 2020. The single greatest obstacle to getting to 750 is the continued high rate of new HIV infections among men who have sex with men (MSM) in New York City.

“My short take is that, at reasonable levels of usage, PrEP is likely to make a noticeable dent in the epidemic for MSM, but alone it’s not going to ‘break the back’ of the epidemic in the ways that would be needed to achieve the numbers in your Plan to End AIDS,” Steven M. Goodreau, a professor at the University of Washington, wrote in an email. “Even in combination with TasP that seems incredibly optimistic.”

PrEP is highly effective when taken daily. PEP, a 28-day course of anti-HIV drugs given to people with a recent exposure, has been used for nearly two decades, but mostly by healthcare professionals with a recent exposure, such as a hypodermic needle stick. TasP also requires strict adherence to dosing schedules among those with HIV.

Goodreau has published 27 peer-reviewed journal articles, with most exploring HIV epidemiology.

In 2012, the latest year for which the state has data, there were 3,316 new HIV diagnoses in New York and 3,141, or 95 percent, were in New York City. Among the city diagnoses, 1,719, or 55 percent, were among men who have sex with men. The rate of new HIV diagnoses among New York City gay and bisexual men has remained stubbornly high for 13 years.

According to city data, there were 1,689 new HIV diagnoses among city men who have sex with men in 2001. That number climbed to 1,873 in 2008 and then fell to 1,609 in 2013, which represented nearly 57 percent of all diagnoses in the city last year. The overall trend in that the rate is stable.

Dr. Demetre Daskalakis. | DONNA ACETO

From 2001 through 2013, every other risk category — heterosexual sex, drug injectors, and mother-to-child transmission — saw substantial declines. In 2013, heterosexual sex accounted for 520 new HIV diagnoses. Injection drug use and men who have sex with men who are injectors combined to contribute 89 cases last year. Mother-to-child transmission caused two cases in 2013. In 2013, “unknown” transmission risk was the next largest group after gay and bisexual men at 612 cases. If the plan eliminates every new infection in these risk categories, it would still have to reduce new infections among gay and bisexual men by more than half to get to 750.

Gay City News wrote or spoke to 11 researchers and authors who have published on HIV epidemiology. Five responded, Goodreau among them, and like him they were skeptical that the goal of 750 new infections by 2020 could be reached.

“It will take a multipronged strategy to make sure we’re tracking down and treating all cases of HIV in all NYC MSM,” wrote Eric T. Roberts, an associate research scientist at the Global Institute of Public Health at New York University and a doctoral candidate at Columbia who published two 2012 articles on HIV prevention in the Lancet.

Roberts wrote that condoms “are still invaluable as a prevention tool” and that “progress from a human rights perspective can help combat issues of stigma and shame,” which is also necessary to fight HIV.

“I’m much more skeptical of PrEP’s role as an HIV prevention strategy,” he wrote, adding that a very high percentage of at-risk gay and bisexual men would have to use PrEP to produce declines in new HIV infections.

Goodreau’s modeling supports that.

“[W]e modeled an average of 40 percent of eligible men being on PrEP at any time,” he wrote. “This led to a 25 percent reduction in prevalence. We also explored 20 percent, 60 percent, and 80 percent… Even at 80 percent, the average reduction was 35 percent. Personally, I don’t see 80 percent as likely ever to happen, but I remain open to being proven wrong on that.”

While the rate of new infections among gay and bisexual men in New York City remains high, it is very likely that TasP and continued condom use have kept those numbers from going even higher. Gay and bisexual men in the city also have very high rates of sexually transmitted diseases (STD), such as syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia, that can facilitate HIV transmission, but there has not been a recent increase in HIV infections that would be expected with more STDs. But what is also notable is that TasP and condoms have not sent those numbers lower, which suggests that the amount of unsafe sex that men who have sex with men are having in the city is defeating the benefits of these interventions.

The state health department did not respond to an email asking about any targets it may have set for the percentage of gay and bisexual who must be on PrEP or what percentage of positive men must be on treatment and have an undetectable viral load for the plan to succeed.