Nowhere in the Middle East have I ever felt afraid as an American. To the contrary, as a gay man who makes my living through travel writing, I have always been welcomed with especially enthusiastic love and hospitality, as most Middle Easterners separate politics from people and are happy to meet us and in turn dispel myths about their own countries.

My sense about the willingness of Middle Easterners to embrace Americans has been reinforced by recent trips I have taken to Afghanistan, Jordan, and Turkey. My Mediterranean coloring no doubt allows me to blend in better than would many Americans, but I think the issue goes far beyond that.

Anyone familiar with Islam knows that hospitality is a major tenet of the religion. How else would a person survive in the desert?

September 11 and the fear it spawned among Americans and other Westerners about the Middle East have decimated the tourism economy there. Remember the economic devastation visited on New York City in the immediate aftermath of September 11, and recognize that the impact in the Middle East has been far more profound. A guide at a Jordanian hotel told me that in the wake of the attacks on New York and Washington, hundreds of his friends lost their jobs, and that even working free/lance once a month, he is considered lucky.

As Ramadan—the holiest month of the Muslim calendar—continues throughout the Islamic world, I begin a series of reports on my recent travels through the Middle East, with a gay twist. As I will discuss in this installment on Jordan, and in later ones on Afghanistan, Turkey, and elsewhere, Americans need to understand and be understood in this very troubled part of the world at this very troubled time, and travel is an important key to that. Hopefully, we can work toward a climate where comfortable travel becomes the norm.

I developed a taste for traveling in the Muslim world in the mid-1990’s during more peaceful times. I visited Israel and Palestine shortly after the Oslo Accords. Crossing the borders was uplifting and joyful—the Palestinians practically hugged everyone coming in—and there were no concrete walls.

Egypt was full of tourists—terrorists had not yet made their mark slaughtering Westerners at ancient temples. Turkey was physically mysterious, its fabled minarets shimmering against twilight waters of the Bosphorus on my first visit. Yet the culture was modern and open, adding comfort to new experiences. Still, each nation was a complete change from the predominantly Christian way of life I had been used to growing up in America.

Since my early travels to the Middle East, times have undoubtedly changed and most of my trips these days are in Latin America. But while attending a Brazil promotion a few months ago at the Times Square Marriott, I got an interesting request. Would I like to see some of the company’s properties in Jordan? I have no fears visiting anywhere—and I knew Jordan to be a very safe place in spite of what many Americans, many of them unacquainted with world maps, think.

Still, there was something unspoken about the trip, a reason why Jordan and the Marriott were promoting the country and the properties now. This was to be no ordinary press trip. Political issues of the moment infused it with a special urgency, and with that, a certain appeal for me. Besides, before Bush makes things worse in the world, I want to see as much of the Middle East as I can.

I consider it judgmental to use the word “progressive” when describing a country’s relationship to its religion, but I don’t know of a better way to explain the difference between Islam in Jordan and Islam in Saudi Arabia. We could of course say the same about progressive Protestant countries like the Netherlands and Denmark versus our own Bible-thumping government.

Jordan is a place where some teenage girls wear midriffs—just like Britney Spears—instead of burqas, and the country has almost always leaned toward Europe and America politically. The U.S. is allowed to keep troops here, for example. Jordan paid for that tilt to the West in the August bombing of its Baghdad embassy.

In promoting its properties in Jordan, Marriott was mindful of its own headlines that it worries about. Its hotel in Jakarta, Indonesia was bombed even though the company has “no reason to believe that we were the target,” according to Kess Connelly, who handles international public relations for the company and was on the trip with me. The Jakarta Marriott sits in a large complex of foreign owned businesses and the bomber, she argued, “was actually trying to get further.”

Jordan is a place I dreamed of visiting since childhood. Yes, it has beaches and palm trees and great food like any world class vacation destination. But it is also the most peaceful country in the Middle East, a gentle desert kingdom, offering a safe refuge to people cast out by war in its neighboring countries—Israel, Palestine, and now, regrettably, Iraq too.

Beyond the politics, it also had an edgy appeal to me as a gay traveler. Overpriced cocktails in Chelsea and South Beach get boring really quickly. I like the mystery of the unknown, especially as it regards a nearly all-male public culture that is clearly homo-social, even if not gay in our sense of the word.

Here in New York, Jordan has been recently been stirring good news. Its famous archeological site, the lost city of Petra, is the focus of an ongoing American Museum of Natural History show. The mid-October Grand Opening was presided over by Queen Rania, herself Palestinian, and considered one of the world’s most beautiful royal women. Modern and liberated, Queen Rania is the physical embodiment of the bridge Jordan tries to build between itself and the West, continuing the work of her predecessor Queen Noor, an Arab American who married into the royal family only a few short years after the OPEC oil embargo.

While here in New York, Queen Rania took time out to stump for Seeds for Peace, an organization bringing Israeli and Palestine children together. Her work on behalf of Palestinians is not merely a show of regional solidarity. More than half of her country is Palestinian, and many of them continue to live in 55-year-old refugee camps established when the United Nations created Israel and Jordan under the same edict. Queen Rania’s days in New York were a calculated peace offering to a media hungry city.

You’d think the ancients must have looked to their oracles and predicted the role Jordan would play in these precarious times. The capital Amman was the original Philadelphia, the City of Brotherly Love William Penn named his colonial burg for, but was made a capital only with the post-war creation of the Jordanian state. Much of the city is very new, with stone and glass structures sprawling on hills cut through by multi-lane freeways.

On foot however, a different city comes into focus. Greek and Roman ruins, rebuilt and then abandoned over the centuries, are the city’s historical highlights. From many points in the city, you’ll see two columns on a high hill. These are some of the remains of the Citadel, a fortress complex built up over a period of perhaps 1,000 years by various civilizations.

From the Citadel, you can easily see the ruins of the Roman Amphitheater, another of the city’s great ruins. It has been partly rebuilt and is surrounded by a colonnade and modern souvenir bazaars. I was climbing the highest points of the arena when the Islamic call to prayer came out. It echoed through the myriad hills of Amman, beautifully reverberating against the theater’s ancient stones. At night, the square surrounding the amphitheater, known as Al-Saha Al Hashemieh, is full of people enjoying the cafes.

It’s also a gay cruising area, and many men came up to say hello. I read that I would also meet gay people at Books@Café (011-962-6-465-0457; m_alijazirah@yahoo.com), a coffee shop and bookstore located appropriately off Rainbow Street. The waiter there, a Palestinian, immediately assured me how safe and open Jordan was, and as an example, volunteered that the café had a gay reputation the owner was happy to maintain. But the waiter also spent time explaining the exiled nature of his Palestinian culture. Just getting coffee it seemed offered an education in both diplomacy and conflict.

The United States is home to more than six million Muslims, but to most Americans, their religion and its rituals remain a mystery. I was in Jordan for the start of Ramadan—the holy fasting month which commemorates the time when Mohammed was given the Koran. A visit to the Islamic world for Ramadan is like traveling to New York for Christmas. It was pure magic to experience the holiday in a country where Mohammed himself once lived.

Ramadan begins the day after the new moon—or crescent moon—is seen in the Islamic world, hence the reason a crescent is the symbol of Islam. That evening, I was alone when darkness fell, so I found strangers to share the experience with. Muslims do not eat in the daylight hours during Ramadan and once the sun went down, Amman became deserted as locals went home share with their families the “iftar” or meal which breaks the fast.

It was a challenge—at which I did not always succeed—to observe the local customs. Not smoking all day was a pleasure—a chance to relax my lungs. But not eating all day was tougher to bear, so I did so discreetly. I bought a small bun in a bakery and found an alley in which to eat it, away from the crowds. I felt like heroin addict when caught in the act, as someone came down the alley and stared at me.

Jordan’s Muslims are certainly better versed in Western religious traditions than we are in theirs. To visit Jordan is to relive the stories of the Torah and the Bible, as well as the Koran. Like Israel, the country is full of sacred sites, most a short ride from the capital.

Among the most significant is Jesus’ Baptism Site on the Jordan River, discovered only in the last decade. You can get baptized here for an only in Jordan experience. My trip coincided with a decidedly more modern event—the Jewel That Is Jordan Bentley Road Tour, in which British car enthusiasts drive the desert in antique cars. The event was part of our tour, and received a royal welcome. Queen Rania dropped from the sky in a helicopter, and choosing between dunking in the river or meeting the Queen, I chose the latter.

Though it’s not as dramatic as walking on water, when you pop out of the sky, crowds will gather. The paparazzi flashed and pushed, while many in the crowd surged forward, forcing her to shake their hands. I decided I would wait to introduce myself and asked her press agent for the right time. The press agent needed to know what kind of publications I wrote for to learn if I were worthy of an introduction, so even though being gay in Jordan is technically against the law, I mentioned, with no small amount of anxiety, my work for the gay press. The queen’s aide let out a small gasped—“Oh!— of surprise. I don’t think anyone had ever said something like that to her before, but that didn’t stop the introduction.

Talking to royalty for the first time in my life, I was tongue-tied but Queen Rania gracefully carried the conversation, speaking mostly about how she enjoyed her time in New York during the Petra opening. Her final words to me were, “But now you are to see the real thing, even better. Welcome.” Then the cameras and the crowds took her away from me.

Only a few miles from the site of the road tour is Mount Nebo, where Moses died. On a clear day, you can see other important religious sites and cities, most less than an hour’s drive away. That’s when I realized how close and yet how far away from real peace in the Holy Land we are. Even Baghdad is no more than 12 hours away, but it seems another planet from this peaceful desert kingdom.

One more incredible site is Jerash, a well-preserved Roman ruin. We visited during the day, and then again at night for a Royal Ball presided over the queen’s brother-in-law, Prince Faisal, and his wife. I came away from the ball with something quite unexpected—a better understanding of neighboring Iraq. The show presented that evening was directed by a troupe of Iraqis and when I introduced myself I found myself more tongue-tied than with the Queen. Our conversation touched on what it was like to live through the American bombing. My Iraqi acquaintances were happy that Saddam is gone, but dispirited by the ensuing mayhem. They mentioned in particular the risk women face today when they are out in public. In the ensuing days I spent with them, the Iraqis also debated the safety of returning home themselves. I wish I could get this troupe to New York, so that the U.S. could have a chance to see Iraqi culture, not just its chaos.

The Dead Sea, the legendary body of water so full of salt and other minerals it supports no fish or wildlife, is another place where Jordan’s proximity to Palestine and Israel is much in evidence. At night, from my hotel room, I saw a small line of lights close to other shore. This is Jericho, the oldest known city still inhabited. More lights on the mountaintop behind it delineated Jerusalem. One can imagine the day when ferries will run across the sea, connecting the cities, promoting tourism and peace and economic prosperity with it.

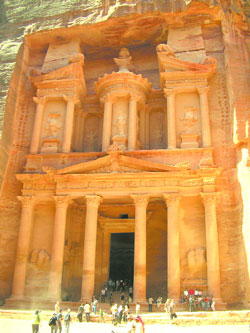

Petra is the most famous site in all of Jordan and a symbol of the country. It has only been known to Westerners for the past 200 years, fiercely kept hidden by the locals knowing, quite correctly, that this magical city might be taken from them in one way or another.

The secret to the location is the long chasm that hides it from view of invaders. Now, one walks through this corridor, cliffs soaring hundreds of feet overhead, in edgy anticipation of when the city will reveal itself. And, reveal itself it does. One is walking along and, suddenly, one of the most famous vistas in all of the world comes into view—the ancient Treasury through a split in the rock.

Though it housed no more than 20,000 people at its height, Petra occupies an enormous amount of space. We call it a city, but most of what you see are not buildings, but tombs carved into the red rock cliffs. Venture into them and you’ll see colorful, almost psychedelic swirls of color in the stones and strange long lines, so perfectly straight, you won’t believe they were done by hand.

Try to stay there for at least two days and include the Petra by Night Tour in your plans. The way to the Treasury is illuminated entirely by thousands of candles. As we walked along, the stars in the clear desert sky above us were the only other light, poking their way through the edges of the dark, silent cliffs.

Bedouins selling jewelry, rocks, and camel and donkey rides will approach you throughout the ruins. The merchants are not particularly pushy, but they can be distracting. But, remember that the Bedouins once lived among the ruins until a government program put them into modern housing to make it easier for tourists to see Petra. Be respectful. You’re a visitor in their home.

Though trading is a Bedouin way of life, I was nevertheless caught off guard by the interesting way some Bedouin men entertain gay tourists. Dreaming of sex in a Bedouin tent under the stars in the ruins of Petra? The place provides.

Bedouin men have intense eyes, some of the world’s most intriguing. I found even the handsomest among them very approachable, and while taking their picture a comment on their looks easily steered the conversation toward sex. Most of the men I met professed to be straight, and bragged about their children. At the same time they claimed that their diet since childhood of camel’s milk—what they called “Bedouin Viagra”—gave them ample endowments, that are instantly aroused at a touch.

In the end, though I enjoyed time alone with one of the Bedouins, and we did more than just talk, it didn’t amount to all that much. No matter how flirty the men are, each insists that the pleasure be all his, and they expect to be compensated on top of that. Their one concession to their partners’ pleasure is that they do take credit cards.

Travel Essentials

Where to Stay: Everywhere I went in Jordan, I stayed at Marriott hotels (marriott.com). The company is working to promote its properties in the Middle East in a harsh economic climate. I usually do not recommend only American-owned properties for travelers, but the Marriott properties are well situated and beautiful, in particular at the Dead Sea Resort, and most of the managers we met are also from the Middle East, helping to keep a local flavor.

Money: The unit of money is the dinar, worth about $1.40. Credit cards and ATM’s accepted everywhere.

———————————–

Electricity: 220 volts, but I saw British, European and American style outlets all over. Bring multiple adapters.

———————————–

Getting there: Royal Jordanian Airlines, direct from NYC 6 times a week; rja.com.jo; 212 949 0050 or 800 223 0470.

Websites: see-jordan.com; www.amnh.org (American Museum of Natural History).

———————————–

Communications: Jordan’s country code is 962 and the web extension is .jo.

We also publish: