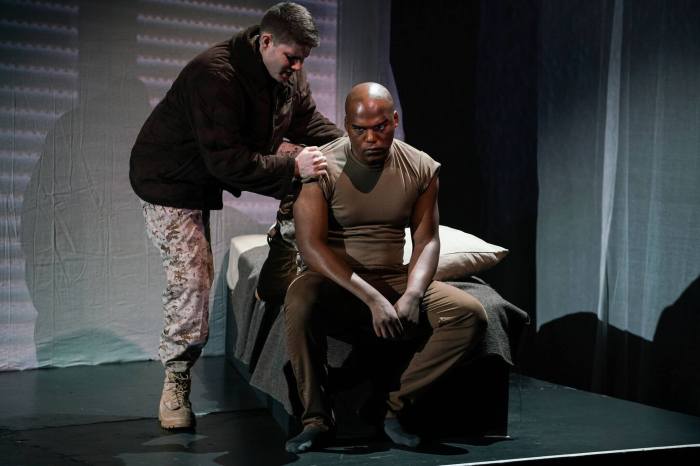

Giorgio Caoduro and Patricia Racette in the Washington National Opera’s production of “Manon Lescaut.” |SCOTT SUCHMAN/ WNO

Washington National Opera revived “Manon Lescaut” for what proved a very strong role debut by Patricia Racette. Heard March 17, the out soprano, looking lovely and youthful (if not teenaged), sounded fresh throughout a long afternoon, mastering everything from trills to high soft attacks. Only the occasional slightly hard high note reminded us that her lyric soprano is a shade small for this Manon. But Racette’s stage savvy and expertise in phrasing and dynamics counted for much; with a resolutely non-Latin sound — evoking her skilled predecessor Dorothy Kirsten, but with much better Italian diction — she provided a touching, masterful portrait.

Racette towered over everything, including Philippe Auguin’s insufficiently urgent conducting and Jake Gardner’s Geronte, a casting that proved an aged Kavalierbariton does not perforce yield a basso buffo. Bulgarian tenor Kamen Chanev, replacing an ailing Fabio Armiliato, was certainly adequate in Des Grieux’s tough part, with some blazing high notes compensating for a weak low range and generalized, conventional acting.

Racette as Manon Lescaut, Stoyanova as Desdemona triumph

John Pascoe’s baroque “story book” production evokes “Beauty and the Beast” (Disney, alas, not Cocteau) in terms of both colors and treatment of chorus. Having “book pages” narrate some of the events in Prevost’s novel uncovered by the libretto has been much copied, but this frame opened and closed too often and too distractingly. Racette and the idiomatic and reasonably good Giorgio Caoduro — playing her gold-digging brother as unusually craven — had fun with Act Two’s comic possibilities. The Dancing Master (Robert Baker) moved well, but Daniela Mack’s Musico did the only distinguished singing among the comprimarios. Lamentably, Pascoe had both affecting fey minstrelsy. But Racette’s new Manon enjoyed a big success.

Attending a Boston Symphony concert in the orchestra’s beautiful hall is always its own reward. It also gives one opportunities to contemplate the differences between that city’s musical culture and ours. College students — unless they’re Juilliard instrumentalists — are among the last segments of New York’s population you’d see at Philharmonic events. Whether due to marketing, demographics, discount policies, or all three, BSO concerts always seem full of them, something that is highly salutary.

The audience, students and all, seemed happier than I was at March 21’s admittedly estimable all-Wagner concert, led by Daniele Gatti, reportedly in the running for chief conductor duties in James Levine’s wake. He programmed orchestral excerpts from “Tannhaeuser,” “Lohengrin,” and the “Ring,” plus Kundry’s solo up through and including “Ich sah das Kind” and Isolde’s Liebestod voiced by Michelle de Young. As in the Met’s recent “Parsifal” run, Gatti took his time — more than his time in many places, with the slightest bar line fermata yielding a l-o-n-g pause. Sometimes there was a payoff, but often the music just sounded unduly distended and disjointed.

Most of the playing per se was excellent, especially in the shimmering “Lohengrin” Act One prelude, which disappointed only in Gatti’s slightly misjudging the climax. De Young remains a real “Zwischenfach” artist, straddling the categories of mezzo and soprano. Her characteristic vocal richness more consistently extends downward — the top sometimes thins out — and though it’s always a pleasure to hear her instrument and musicianship, the interpretive textual impulses emerge rather generalized.

Riccardo Zandonai’s “Francesca da Rimini,” heard March 22, was worth reviving — it’s an often fascinating post-Wagnerian score and the Met’s lavish production has its delights — but the romantic leads lacked both chemistry and the wild obsessive identification with the iconic roles that “Francesca” needs to breathe. Eva-Maria Westbroek’s heroine looked and moved well, and she acted with intelligence. The voice glows attractively save for on high Bs and Cs, fallen victim here perhaps to roles like Puccini’s Minnie. By and large, however, Westbroek lacks the verbal bite and clarity the high-octane text needs.

Marcello Giordani’s tenor was hard-pressed as Paolo il Bello. He got most of the notes out, almost all of them at forte dynamics, and native Italian helps, but there was little light or shade here. Stolid, he left acting largely up to Westbroek.

Mark Delavan managed to make the bluff, misshapen Gianciotto somewhat sympathetic; the part suits him temperamentally and vocally. Robert Brubaker, always a stage animal, lit into the nasty Malatestino’s music with gusto and a penetrating if hardly dulcet tone. Some — not all — small parts were cast from strength. My ears caught very fine work from Dina Kuznetsova (Samaritana), Caitlin Lynch (Biancofiore), Keith Jameson (Toldo), and especially the clear baritone of John Moore (Simonetto) and Jerry Grossman’s expressive cello. Marco Armiliato was a low-key, idiomatic interpreter, while Zandonai’s creative but overheated orchestration needed something rather more really to flourish.

“Otello” (March 27) found Alain Altinoglu in the pit trying to cope with a leading tenor wayward of pitch, note values, and rhythm. Every once in a while, José Cura would make a sound that reminded one he was once a promising vocalist. Most of the time, though, it was dry, husk-like off-pitch noise. Though he largely played Otello as a depressive, Cura has the physical mobility and stage smarts that poor Johan Botha so lacked in the role this past fall. At the end he proved quite moving. But Otello is simply no longer within his voice’s capabilities. What is — Strauss’ Aegisth?

By contrast, Krassimira Stoyanova’s proud, straightforward Desdemona, ravishingly voiced with great skill in dynamics and phrasing, stands among the season’s best individual performances. The debuting Marco Vratogna, as Iago, had the active virtue of not being Thomas Hampson — a fine artist in his natural repertory, which is to say not remotely the Verdi heavies he’s exploring now. Vratogna’s other virtues included native Italian and a decent Verdian sound — stronger at the top than the bottom, which could waver. He made a reasonable presentation of the character — bluff rather than elegant, but creditable, especially for a first-ever night at the Met. Vratogna should make a good Ford in “Falstaff.”

Alexei Dolgov, new this spring, joined the fall’s Michael Fabiano in a club of luxurious leading tenor Cassio castings. Jennifer Johnson Cano’s Emilia and Alexander Tsymbalyuk’s ear-catching Lodovico marked improvements from the autumn HD cast.

David Shengold (shengold@yahoo.com) writes about opera for many venues.