“The Most Beautiful Boy in the World” works overtime to convince the spectator that its subject, former child actor Björn Andrésen, is damaged goods. Cast at 15 to play Tadzio in gay director Luchino Visconti’s 1971 film “Death in Venice,” his life was changed forever by the experience. But Swedish directors Kristina Lindstrom and Kristian Petri’s documentary is so manipulative that one wonders about the gaps and omissions in its presentation of Andrésen’s life as 65 years of sheer misery.

“The Most Beautiful Boy in the World” uses techniques from fiction to enhance its depressive mood. Andrésen is filmed walking through hotel corridors, forests, and beaches in slow motion. In and of themselves, these images are innocuous, but on the soundtrack, he talks about some of the worst moments of his life. The score, composed by Anna von Hausswolff and Filip Leyman, serves up melodramatic sturm und drang. The dim cinematography suggests the darkness of Andrésen’s story. At the end, the film cross-cuts between the present-day Andrésen on the beach and images of his 15-year-old self in a similar location from “Death in Venice.” “The Most Beautiful Boy in the World” goes back and forth between the young and old Andrésen, who retains the long hair he had as a teenager, for shock value, framing him like a “Game of Thrones” character. The message couldn’t be any more obvious — the promise Andrésen had as a teenager was destroyed. His most recent acting role, as a cultist who leaps off a cliff to his death in Ari Aster’s ‘Midsommar,” seems all too apt.

I don’t doubt the truth of this film’s thesis, but it’s full of strange omissions and ellipses. Andrésen is shown composing music and playing the piano, but the film fails to connect this to the period just after “Death in Venice” when he became a pop star in Japan. In fact, Andrésen attended school for music training and made a living as the band Sven Erics’ keyboardist for many years. But this part of his life is relegated to the background. He also acted in a film before “Death in Venice,” but this is never mentioned.

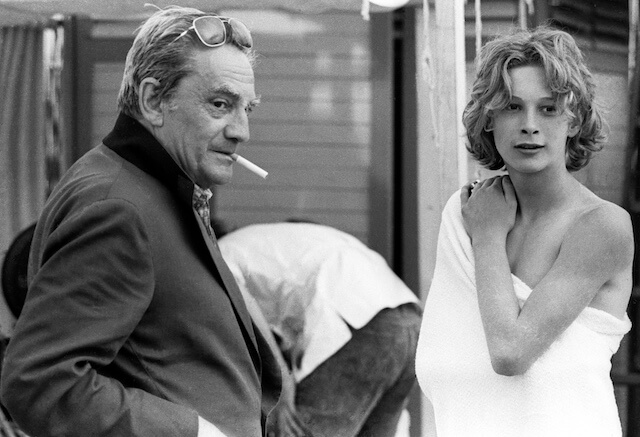

Revisiting “Death in Venice” leads to some extremely fraught territory. Thomas Mann, who wrote the original short story in 1912, was inspired by his attraction to an 11-year-old boy. The story itself does not condone pedophilia; indeed, Aschenbach, its middle-aged male protagonist, dies partially as a result of his desire for the boy. (In the film, he’s played by gay actor Dirk Bogarde.) Both the book and film can be read in more metaphorical ways, especially a comment on the danger of idealizing beauty and youth. (In “The Most Beautiful Boy in the World,” Visconti describes Aschenbach feeling a love “neither erotic nor sexual” for Tadzio.) But that’s just what the film does, treating Tadzio, and by extension Andrésen, as a mysterious icon who turns out to be an “angel of death,” not a full-fledged person.

Andrésen is straight, but he spent a time in Paris as a sex worker living with wealthy sugar daddies. Although he’s not explicitly homophobic, his experiences seem to have led him to see gay men as creeps lusting after teenage boys. The film doesn’t do a good job of differentiating between gayness and pedophilia. It suggests that because the crew in “Death in Venice” was almost all gay, they lusted after the 15-year-old Andrésen, and that when Visconti took him to a gay bar, all its patrons wanted to sleep with him. These aspects of making “Death in Venice” were undoubtedly true, but the film is so tightly focused on Andrésen’s story that it misses larger issues about child exploitation in the film industry. It feels unaware that its depiction of his objectification is a microcosm.

While it suggests that performing in “Death in Venice” ruined his life, it drops several other tragedies of Andrésen’s life into the film in intervals that suggest a three-act structure. In 1966, his mother disappeared and then turned up dead in a forest. This meant that he had little adult supervision as a child and teen, with no one to look out for him while making “Death in Venice” and living through the fame it brought him. Then, his eight-month-old son died of SIDS. His grief led to depression and problems with alcohol.

“The Most Beautiful Boy in the World” is moving, but the path to those emotions seems heavily massaged. Details of Andrésen’s present-day life are brought up for their shock value but dropped. At the start of the film, he’s about to get evicted from his filthy apartment (for, among other things, leaving his stove’s burner on constantly through the winter.) In a conversation with his partner, she says that he kept her under virtual house arrest on a trip to Japan. But the potentially ugly aspects of his own behavior are elided in favor of turning him into a martyr. The film is a potent demonstration of the danger of objectifying youth. But it transforms a real person into a pillar of misery, ignoring anything that could complicate this picture. And if living in the spotlight damaged Andrésen’s life, is pushing him back into it by making him a documentary subject a responsible act?

THE MOST BEAUTIFUL BOY IN THE WORLD | Directed by Kristina Lindstrom and Kristian Petri | Juno Films | In Swedish with English subtitles | Opens at the Quad Cinema Sept. 24th