Eva-Maria Westbroek (center) as Katerina in Shostakovich's Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. | KEN HOWARD/ METROPOLITAN OPERA

BY ELI JACOBSON | Some operas take a while to click with audiences — it may take a revival with the right cast and a crowd receptive to its message. The Metropolitan Opera’s current revival of Dmitri Shostakovich’s scandalous 1934 opera “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk” is a case in point.

When the Graham Vick production premiered in 1994 — has it really been that long? — the music seemed loud and empty and the production pointlessly busy, vulgar, even tacky. It was not helped by a sullen, vocally underpowered Katerina who had no chemistry with her tenor love interest for whose sake the titular anti-heroine commits three murders.

And a good girl in a gondola through the ages

For this 20th anniversary revival, Vick was invited back to direct a sexy, dramatically volatile new cast and the pieces all came together. It played like a fresh, electrifying new production, not a revival. James Conlon leads the superb Met orchestra and a revitalized protean chorus with authority and sweeping drama. At the final bows at the revival premiere on November 10, the Met audience rose to its feet in a genuinely enthusiastic standing ovation, and when the curtain finally descended, cheers erupted backstage as the cast hooted and hollered in triumph.

Eva-Maria Westbroek’s Katerina, bleached blonde and a little frowsy in a cheap floral print dress, is a frightening portrait of the banality of evil. She charts Katerina’s progress from a bored, unfulfilled housewife to an empty-eyed killer — this profoundly shallow woman decides that an orgasm is worth killing for and annihilates anything that interferes with her fulfilling her lust. Even in the Siberian prison camp there is something chillingly childlike about this woman.

Tenor Brandon Jovanovich is all testosterone, pheromones, and false promises as her adulterous lover Sergei. Frequently stripped down to his tighty whities, his burly baritonal tenor is as irresistible as his hairy, burly frame. Their erotic connection is palpable and fully believable — the two go through the entire Kama Sutra without missing a note. Westbroek’s smoldering, unsettled, overripe soprano embodies the desires driving her character, a few weak wobbly high notes aside.

Anatoli Kotscherga’s characterful Slavic bass reeks of stale breath, cheap vodka, and arrogant bile as Katerina’s repellent father-in-law Boris. Raymond Very’s sweet lyrical tenor makes Katerina’s ill-fated husband Zinovy an appealing and sympathetic victim. Three basses — Mikhail Kolelishvili as the Priest, Vladimir Ognovenko as the Policeman, and the mournful beauty of Dmitry Belosselskiy’s Old Convict — provide unforgettable cameos. The chorus had to range from shirtless workmen cavorting in the yard to a line of broken prisoners marching through the gulag.

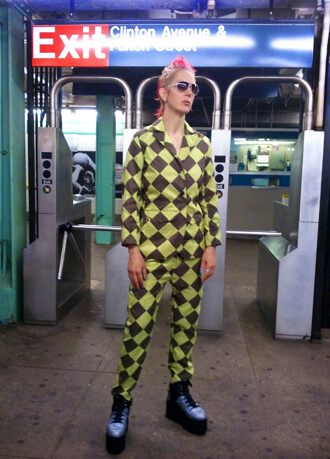

Vick’s riotous, colorful production, updating the action to the late 1960s, embraces the cheap vulgarity of the new Russian culture — Katerina’s wedding with Sergei is reminiscent of Brighton Beach nightclubs down to the tacky tuxedos, short skirts, and mirror ball. The surreal insanity of the staged interludes — murderous drag queen brides and mad housewives vacuuming the walls — provided needed levity and satire. Stalin hated it but the opening night audience loved it. This is one of the don’t-miss events of the season.

Joyce DiDonato presented “A Journey Through Venice” at Carnegie Hall on November 4.CHRIS LEE/ COURTESY OF CARNEGIE HALL

Joyce DiDonato is this season’s ubiquitous golden girl with a new production of “La Donna del Lago” at the Met. Her season-long residency at Carnegie Hall includes a concert performance of Handel’s bad girl opera “Alcina,” various concerts, and a main stage Carnegie Hall recital on November 4 with her usual accompanist, David Zobel.

The recital, entitled “A Journey Through Venice,” explored that city not just as a place but as a state of mind. Or more accurately, various states in different eras: from the baroque Venice that produced Vivaldi’s opera “Ercole su’l Termodonte,” from which DiDonato sang two elegant arias, to the darker ottocento Venice of Rossini’s “Otello,” where Desdemona dies for her love in the “Willow Song.” The mercurial Rossini then explored the rowdy street carnival side of Venice in his “La Regatta Veneziana” cycle.

A mysterious, sinister, unknowable Venice emerges in 20th century British composer Michael Head’s “Three Songs of Venice.” Reynaldo Hahn’s “Venezia” cycle evokes the tourist Venice of gondolas, summer afternoons, and romance, while Gabriel Fauré in his “Cinq mélodies de Venise” evokes an impressionistic decadent Venice, home of the true aesthete.

DiDonato’s voice was equally chameleonic as she explored each of these Venetian landscapes. Her coloratura rippled and sparkled like a clear stream in the sunlight in Vivaldi’s arias for the innocent Ippolita. In the Fauré cycle, her sensual tone turned smokier and more transparent, giving light and shade to the perfumed melodies. Rossini’s Desdemona had a more complex pomegranate timbre and a more extroverted operatic manner. Rossini’s Anzoleta cheered on her gondolier lover in the regatta with an earthier but still sunny tone and just enough dramatic action to illustrate the songs.

Here or there DiDonato’s forte high notes tighten and whiten, developing a fast rattly vibrato — about the only vocal flaw in her technical arsenal. In the Head songs, an outsider observes a gray, misty Venice that seems to draw one in and yet elude one simultaneously. DiDonato’s hushed, covered sound evoked both the shadows and mists of this Venice but also the cycle’s creator, Dame Janet Baker. The Hahn cycle showed the mezzo’s sunny, earthy, and seductive sides in turn. Singing in three languages, DiDonato always works off of the text, giving each moment a personal connection.

She was more dramatic in the opera arias, seductively intimate in the songs, always giving a sense of dramatic context. Zobel’s piano accompaniment proved stylistically adept in the elusive French songs and was keenly supportive throughout. DiDonato’s voice is not a remarkable instrument in and of itself though it is very agile and attractive — it is not great in size or unique in color. But she is a communicator who connects with the material and the audience, taking them on a very personal journey. In speech or song, Joyce is a charmer. I, for one, would follow her anywhere.