Fayetteville has been a welcome hotbed of LGBT rights advocacy in recent years, but on February 23 the Arkansas Supreme Court, reversing a ruling by Washington County Circuit Court Judge Doug Martin, found that the city and its voters violated state law by adding “sexual orientation” and “gender identity” to their antidiscrimination ordinance. Justice Josephine Linker Hart wrote the opinion for the unanimous court.

Responding to earlier attempts to enact LGBT rights protections in Fayetteville, the Arkansas Legislature, in 2015, passed the Intrastate Commerce Improvement Act, intended “to improve intrastate commerce by ensuring that businesses, organizations, and employers doing business in the state are subject to uniform nondiscrimination laws and obligations, regardless of the counties, municipalities, or other political subdivisions in which the businesses, organizations, and employers are located or engage in business or commercial activities.”

The measure bars local governments from enacting “an ordinance, resolution, rule, or policy that creates a protected classification or prohibits discrimination on a basis not contained in state law,” except on the question of their own municipal employment policies.

Sexual orientation, gender identity, though mentioned in state law, cannot be protected anti-bias categories

Like the rest of the American South, Arkansas does not forbid sexual orientation or gender identity discrimination in its state antidiscrimination statute. The clear intent of Arkansas legislators two years ago was to preempt local governments from adding those two characteristics to their local laws. Or at least that’s what the state’s high court held in this decision.

Local LGBT rights advocates and city officials took a different view, however, seizing on the literal meaning of “not contained in state law” and finding that some Arkansas laws did mention sexual orientation or gender identity. An anti-bullying law protects public school students and employees from bullying because of gender identity or sexual orientation, among a list of 13 characteristics. There is also a provision in the state’s domestic violence law requiring shelters to adopt nondiscrimination policies that include “sexual preference.” And the state’s vital statistics act provides a mechanism for an individual to get a new birth certificate after sex reassignment surgery.

Taken together, the advocates argued that “sexual orientation” and “gender identity” are classifications that exist in Arkansas law, so their inclusion in Fayetteville’s anti-discrimination ordinance would not be prohibited by the 2015 state law.

Just months after the Legislature approved that, the Fayetteville City Council adopted a new ordinance adding those categories to its local nondiscrimination ordinance, subject to voter approval. In September 2015, voters confirmed the Council action by a 53-47 percent margin.

Opponents of the measure, organized as Protect Fayetteville, first tried to forestall that referendum, but failed, and so became plaintiffs in the lawsuit that prevailed last week.

At the trial court, Justice Martin accepted the argument that since that “sexual orientation” and “gender identity” are categories mentioned in state law they could be added to the local nondiscrimination ordinance. The Supreme Court’s reversal was premised on legislative intent.

“In this case,” wrote Justice Hart, “the General Assembly expressly stated the intent” — namely to have nondiscrimination laws uniform through the state.

The Fayetteville ordinance, she noted, stated that “its purpose is to ‘extend’ discrimination to include ‘sexual orientation and gender identity… In essence, Ordinance 5781 is a municipal decision to expand the provisions of the Arkansas Civil Rights Act to include persons of a particular sexual orientation and gender identity.”

That’s an incorrect interpretation, of course, since sexual orientation and gender identity protections cover straight and cisgender people just as much as they do gay, lesbian, and transgender people.

Still, she asserted, “This violates the plain wording of Act 137 by extending discrimination laws in the City of Fayetteville to include two classifications not previously included under state law. This necessarily creates a nonuniform nondiscrimination law and obligation in the City of Fayetteville that does not exist under state law.”

The result, the high court found, is “a direct inconsistency between state and municipal law and… the Ordinance is an obstacle to the objectives and purposes set forth in the General Assembly’s Act and therefore it cannot stand.”

She noted that the state laws that the city and Judge Martin pointed to to justify adding these categories were not antidiscrimination statutes, and so could not be relied upon as a basis for adding them to the Fayetteville antidiscrimination ordinance.

The State of Arkansas intervened in this case to protect the constitutionality of its 2015 law, which had been questioned by the city, but that issue was not addressed by the circuit court, so the Supreme Court found it had not been preserved for appellate review. Now that the case is returning to the circuit court level, the city can pursue that issue there.

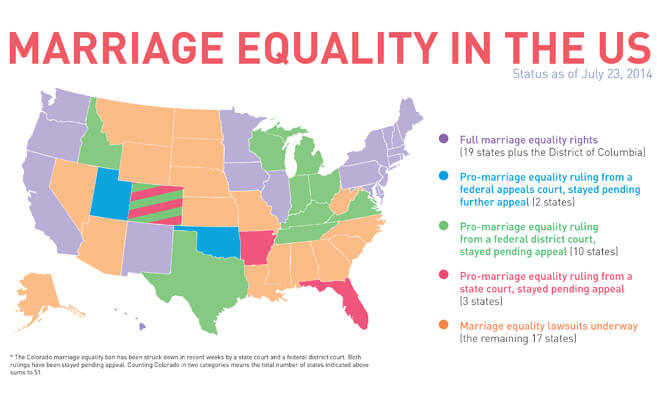

Despite it euphemistic language, the 2015 Arkansas law is strikingly similar to Colorado’s Amendment 2, which was declared unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment by the US Supreme Court in Romer v. Evans in 1996. Amendment 2 barred the state or any political subdivision from prohibiting discrimination because of sexual orientation, and the Supreme Court condemned it as intended to make gay people unequal in exercising their political rights to everybody else, based on the voters’ moral disapproval. Colorado advanced a desire for uniformity of state laws as one of many justifications for Amendment 2. Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing for the Supreme Court, did not specifically reject any of the state’s justifications, but stated that none was sufficient to sustain the law.

Even at the lowest level of judicial scrutiny — that it have some rational basis — Amendment 2 could not survive, the nation’s high court found.