Justin Walker, recently confirmed by the Senate to be a judge on the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, completed some unfinished business on his docket as a US district judge in Louisville, Kentucky, by issuing an order barring the enforcement of that city’s public accommodations nondiscrimination ordinance against a recalcitrant wedding photographer.

Chelsey Nelson is a photographer whose business includes weddings. She’s never been asked to photograph a wedding of a same-sex couple but claims that her religious beliefs would compel her to refuse — and she would like to avoid such confrontations by advertising on her website that she will not provide such service.

Louisville, in 1999, became the first municipality in Kentucky to ban anti-gay discrimination, and its ordinance prohibits businesses from denying patrons goods or services because of their sexual orientation and from communicating to the public that they will refuse such service.

Represented by Alliance Defending Freedom, the anti-LGBTQ litigation group, she filed a lawsuit seeking a court order that she is not required to comply with the ordinance and can publish her views without liability. She claims the ordinance has chilled her exercise of her constitutional freedom of speech and free exercise of religion rights under the First Amendment by deterring her from using her website to communicate her message.

Trump judge bars enforcement of Louisville anti-bias laws in suit claiming free speech, free exercise rights

Louisville Metro Human Relations Commission has stated that Nelson’s action would violate the city ordinance and has not “disavowed” any intention to prosecute if she were to proceed.

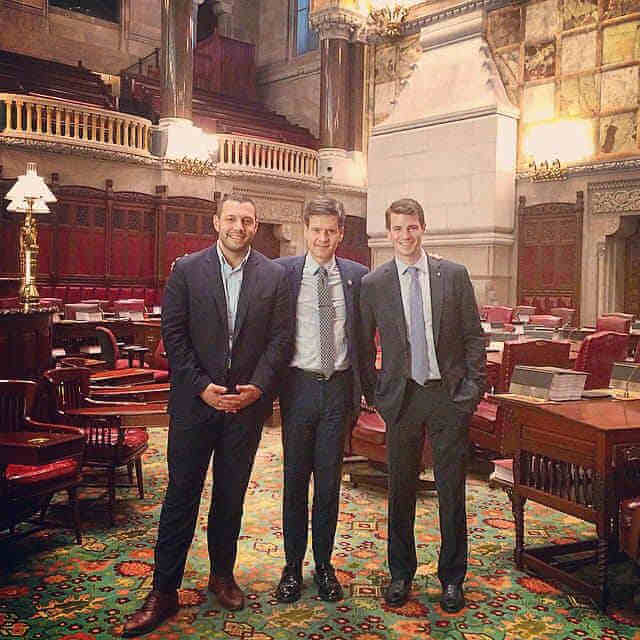

Judge Walker is a family friend and protégé of Senator Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who recommended his appointment to President Donald Trump and shepherded his nominations — first to the district court and then to the DC Circuit Court — through confirmation votes. Walker is a leader of the conservative Federalist Society branch in Louisville, where he worked as a lawyer and professor before taking the bench.

Walker’s August 14 order denied the city’s motion to dismiss the case and granted, in part, Nelson’s motion for a preliminary injunction against the city enforcing the law against her pending a trial on the merits of her claim. Though praising the activists who campaigned to have the gay rights ordinance adopted more than two decades ago, Walker — who, born in 1982, could have a long career on the bench ahead of him — concluded that Nelson has a good chance of prevailing in the end, a conclusion that is a prerequisite for ordering a temporary bar on enforcement of a law that, on its face, is not unconstitutional.

Walker premises his conclusion by referring to the Supreme Court’s unanimous 1995 decision in Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Group of Boston, in which the court ruled that the St. Patrick’s Day Parade organizers there were not required to allow a gay Irish-American group to march if the organizers did not want to include a gay rights message in their parade. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court had ruled 4-3 that the state’s public accommodations law, which prohibited sexual orientation discrimination, required the parade organizers to let the gay group march.

In reversing, the Supreme Court found that the parade was an expressive activity protected by the First Amendment’s freedom of speech provision. Forcing the organizers to include the gay group would be unconstitutional compelled speech, the court held, imposing the gay group’s message on the parade organizers’ expressive activity.

Walker embraced the analogy to requiring a photographer to take pictures she did not want to take as compelled speech, and that the provision making it unlawful for her to publicize her refusal to photograph same-sex weddings was a content-based restriction on her speech. Because her speech was motivated by her religious beliefs, the constitutional problem was compounded, in Walker’s view, who noted that the Supreme Court has found that government-compelled speech and punishment of religious expression impose irreparable injury, another test for the preliminary relief he granted Nelson.

Court decisions on this issue are divided. In 2013, New Mexico’s Supreme Court found that a wedding photographer violated the state’s public accommodation law by refusing to photograph a same-sex commitment ceremony, and the US Supreme Court declined to review that decision.

But more recently the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of a videographer who did not want to film same-sex weddings, and the Arizona Supreme Court ruled that a custom stationery business did not have to create invitations for a same-sex wedding, both relying on First Amendment free speech rights.

What the more recent cases have in common is that they are part of a broader litigation strategy by Alliance Defending Freedom and other conservative litigation groups, which having lost the battle against marriage equality seek to establish broad constitutional exemptions from having to comply with anti-discrimination laws regarding same-sex wedding services. These are “affirmative litigation” cases brought to challenge the application of these anti-bias laws. They do not entail the actual denial of service to an individual, unlike the famous Masterpiece Cakeshop case in Colorado or similar ones where same-sex couples have filed discrimination claims after being denied goods or services.

Louisville could appeal the preliminary injunction to the Cincinnati-based Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals or could wait for a final ruling on the merits before filing an appeal.

Local media coverage of the case has undoubtedly solved Nelson’s problem of communicating her stance to the public, so it seems unlikely that any same-sex couples planning their weddings in Louisville are going to approach her.

The injunction specifically protects Nelson from being investigated by the Louisville Commission, but does not prevent the Commission from enforcing the ordinance against any other business violating the anti-discrimination ban, so there is no pressing urgency for an appeal.

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter.