Ever see a movie so “well-made” and “beautiful” it becomes suffocating?

Gerard Bush and Christopher Renz’s “Antebellum” attempts to show the persistence of slavery in modern-day America. But it does so through a gimmicky narrative, divided so carefully into three acts that it would embarrass a screenwriting teacher. Without spoilers, the film contains a twist that’s neither clever nor original. (Octavia Butler’s novel “Kindred,” Haile Gerima’s film “Sankofa” and, more generally, “The Twilight Zone” are obvious influences.) Bush and Renz’s background lies in “social justice”-minded commercial work. They tried to make a genre film with the same mindset and have fallen flat on their faces.

Chronicling white supremacy’s persistence with superb technique, but little sense of narrative proportion

“Antebellum” starts with a very long, gliding Steadicam shot that takes us from the exterior of a Southern plantation to its depths, where Black people are being beaten, over the course of several minutes. Although editing trickery has obviously been used to conceal cuts, the choreography that must have gone into setting up the shot is impressive. Bush and Renz have an incredible eye for framing. One scene manages to echo “Gone with the Wind,” Nazi marches in 1930s Germany, and the 2017 rally in Charlottesville, Virginia all at once. The problem with “Antebellum” is that the filmmakers never pass up an opportunity to remind the spectator how skilled they are, even in situations where it’s wildly inappropriate.

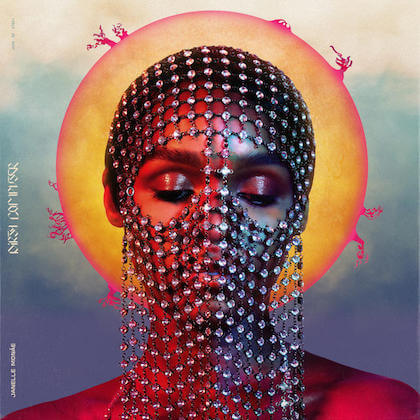

Eden (pansexual singer Janelle Monáe) toils on a plantation while the Civil War is taking place. Having just been recaptured after an escape attempt, she’s stoic and numb. She spends her days picking cotton under the supervision of Captain Jasper (Jack Huston), while the factory owner, simply called Him (Eric Lange), tortures her in an early scene and frequently rapes her at night. But then Eden wakes up and transforms into Veronica (also played by Monáe), a wealthy and successful writer in present-day America. Were Eden’s experiences simply Veronica’s nightmare?

While still a film critic for Cahiers du Cinéma, Jacques Rivette wrote an essay attacking Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1960 concentration camp-set “Kapo” for aestheticizing such conditions with a zoom that moved in to reframe its heroine’s corpse. If Rivette were still alive, he would recognize the same ethos at play in “Antebellum” and walk out after 15 minutes. When Eden is branded, the camera moves closer to catch her pain and then backs away slightly. The film then serves us a “painterly” vista, with her slave owner riding off as the moon glows invitingly in the upper right of the screen.

Bush and Renz have a gift for visual style on the most basic level, but no idea when it might be inappropriate. One can tell that they’re trying to parody the look of “Gone with the Wind” at times, but much of “Antebellum” feels like a cinematographer’s demo reel.

It’d be putting it kindly to say their script is heavy-handed. Promoting her book “Shedding the Coping Persona,” Veronica lectures an audience of Black women about “liberation, not assimilation” in a scene that plays like a TED talk. Back on the plantation, a mustachioed, thickly accented man tells a line of Black girls that they can’t speak until spoken to by whites and, for extra creepy affect, grabs the cheek of one girl.

A few neat touches reflect the long-lasting impact of slavery and white supremacist ideology: Veronica stays in her hotel’s Jefferson Suite, but strides through an airport lobby in colorful African-influenced clothes while everyone else is dressed in dark suits. Monáe’s performance is superb, taking her character from beaten-down pain to hard-won pride to desperate violence while maintaining a through-line at all times. But the directors are terrible at pacing. The middle third feels padded. The camera circles endlessly around Veronica and her friends for no apparent reason as they eat dinner.

The problem with “Antebellum” isn’t that it was made by a white person who’s distant from the real pain and oppression it depicts. Bush and Renz are an interracial gay couple; Bush is Black. But its sensibility is closer to a ‘70s B-movie than “Get Out,” although its publicity materials proudly trumpet the fact that its production company QC also worked out on that film. (Had Jordan Peele had any input into “Antebellum,” it likely would have turned out better.) Its pretense of depicting the overlap between America’s racist past and present feels dishonest when it leads to an action movie about a slave revolt that isn’t nearly as good as “Django Unchained,” followed by the reveal of its gimmick.

The final image before the closing credits of “Antebellum” reminds us how America has covered up its tragic history by turning it into entertainment. Is this film self-aware enough to realize it’s part of that process too?

ANTEBELLUM | Directed by Gerard Bush and Christopher Renz | Lionsgate | Starts streaming Sept. 17 | lionsgate.com/movies

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter.