VOLUME 3, ISSUE 344 | October 28 – November 3, 2004

Free Speech In Wartime

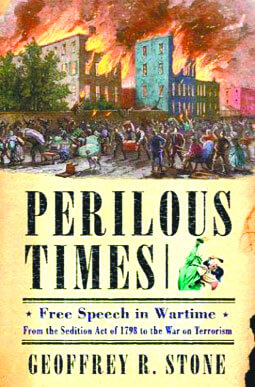

W.W. Norton & Co.

684 pages; $35

The First Amendment in Wartime

Author canvasses suppression of dissent through American history

All societies live by myths, and no society can live without them. Myths are narratives that furnish the organizing principles for society and its culture. Myths make life within society tolerable, meaningful—indeed, possible.

America, too, lives by and through its myths. At various points in its development, American culture fostered the nation-building myth of manifest destiny, the capitalist myth of the unregulated marketplace and the political myths of civic democracy and social equality.

Among the greatest of America’s myths, however, is that of the First Amendment—that we, as a society, trust in a free marketplace of ideas and beliefs to discover our governing truths, and that we, as a polity, invite and protect civic dissent.

One key purpose of the First Amendment, properly understood, is to teach toleration for political and social dissent and to uphold the expressive rights of dissenters. At its best, the First Amendment creates a safe haven for ranters who debunk society’s entrenched values, so as to open our eyes to new perspectives. At its worst, when the First Amendment fails in its great mission—it permits the persecution and prosecution of our value-busters.

Unquestionably, the noble myth of the First Amendment malfunctions most seriously in times of war or anticipated war. It is then that our nation’s leaders and much of its citizenry have too often been willing to trade a full measure of speech freedom for the illusion of greater security. Our expressive liberties have been most endangered precisely when they should have been most engaged.

So it was in 1798 when American fears of an impending war with France were whipped up by the Federalist administration of Pres. John Adams. Congress passed the first federal Sedition Act, which criminalized any malicious criticism of the government. No French sympathizers were ever found and prosecuted, but the Act was enforced against members of Thomas Jefferson’s Republican Party who challenged Federalist policies.

So it was in World War I when, fearing German-American spies, Congress passed the 1917 Espionage Act and the 1918 Sedition Act. More than 2,000 prosecutions were brought under those laws before and after the armistice, and more than 1,000 convictions were secured, almost all of them for questioning conventional beliefs that the American war effort was principled and righteous. A minister was sentenced to 15 years for preaching that the war was “un-Christian.” A newspaper editor served time for writing that the war was the work of Wall Street. And Eugene Debs was imprisoned for a similar “crime”—declaring the war to be a capitalist plot. Not a single traitor was discovered, but political dissenters, pacifists and labor radicals were silenced.

So it was again in World War II, when tragic trades of liberty for ostensible security were made during the 1940s with the West Coast relocation and internment of Japanese Americans and with federal and state “witch hunts” of socialists, fascists and Communists accused of conspiring against military recruitment or advocating the violent overthrow of government.

And the “devil’s bargain” of liberty for security was struck once more between 1951 and 1956 as congressional McCarthyism supported the fanatical myth of Communist infiltration of the federal government by suppressing unpopular political ideas and associations

These sordid chapters of American free speech history – and several others—are the subjects of Geoffrey Stone’s masterful book, “Perilous Times.” Former dean of the University of Chicago Law School and lead author of a respected constitutional law casebook pored over annually by thousands of American law students, Prof. Stone has applied his formidable talents to examining the political and legal battles over First Amendment rights of civic dissent in seven periods of American history: the “half war” with France, the Civil War, the First and Second World Wars, the Cold War, the Vietnam War and our current “war on terrorism.

This remarkable compendium of free speech history is likely to reach a pinnacle of success that eludes most historical tracts because it can appeal to an extremely broad audience of different professions, interests and political perspectives.

The legal practitioner or jurist may be most intrigued by Stone’s absorbing accounts of the factual backgrounds and rulings in seminal First Amendment wartime cases (from Masses, Schenck, Debs and Abrams through Dennis and Yates to more current decisions that cast doubt on those precedents). Happily, Stone’s analysis of judicial doctrine is delivered in a dynamic and non-jargoned prose style that enables lawyers and lay readers alike to understand the case law; and his critiques of the cases are thoughtful, poised and even-handed enough to ruffle the feathers of card-carrying liberals and code-carrying conservatives alike.

For the college or law student and the educated non-lawyer, Stone provides fascinating narratives of the socio-political contexts that set the stage for wartime free speech struggles. Readers learn of the presidents (the purportedly speech-protective Lincoln versus the speech-repressive Adams, Wilson, Roosevelt, and Nixon); the attorneys general (the speech-respectful Frank Murphy, Robert Jackson and Francis Biddle posed against the speech-disrespectful John Mitchell); the federal lawmakers (from Congressman Matthew Lyon, the first person indicted under the Sedition Act of 1798, to Congressman Martin Dies, the first chairman of the House Un-American Activities Committee, and Sen. Joseph McCarthy, who conducted a Cold War campaign of character assassination on scores of alleged Soviet spies); the educators (especially University of Chicago’s President Robert Maynard); and the activists (such as Vietnam War protestor David Dellinger of the Chicago Seven fame)—all who played prominent roles in First Amendment history.

Through colorful anecdotes on such figures, Stone demonstrates that our First Amendment freedoms depend not only on enlightened judges, but on a full spectrum of liberty-loving public officials and private citizens.

“Perilous Times” should also impress legal historians and constitutional scholars. It is exhaustively researched, and its detailed and informative endnotes comprise 132 pages of eight-point text. Academics accustomed to the obsessive-compulsive citation practices of university law reviews and legal practice journals will not be disappointed by Stone’s thorough source authority.

Beyond those audiences, anyone who truly cares about the American culture of civil liberties will appreciate the critical lessons that emerge from this voluminous free-speech history. There are at least four such lessons.

First, our federal and state governments have suppressed political dissent most virulently when there was a collective sense of wartime threats to national security. Second, with the acuity of hindsight, thoughtful persons have seen that public officials, the media and private citizens typically overreacted real free speech dangers were not as great as anticipated, and legitimate civic dissent paid an unacceptable price. Third, in the worst of these periods, public leaders intentionally fueled the fires of speech repression rather than tamping them down, often to serve their own partisan or personal interests. And fourth, to keep the First Amendment from turning cyclically into a dysfunctional myth in wartime, Americans must steel the national cultural psyche in advance.

Stone recommends, among other salutary steps, that Congress adopt rules and protocols (e.g., full committee investigation before enacting wartime legislation, “sunset” provisions for speech-restrictive measures, and others) to check itself and the other branches of government from overreacting to public fears and exaggerating free speech perils. More importantly, Stone reminds us that a culture of free speech will require the efforts of all public and private institutions—education, media, the legal profession, civil liberties organizations—to teach the most important lesson in defense of civic dissent: that fear is the first enemy of freedom.

No work of this generous character is flawless, and “Perilous Times” has a few faults, albeit minor ones. For a volume that apparently aspires to encyclopedic stature, the book gives merely passing reference to the repressive experiences of anti-war dissenters in the War of 1812, the Mexican War and the Spanish-American War. To study those episodes, Stone’s readers must turn to the excellent (and, unfortunately, out-of-print) book by Samuel Eliot Morison, Frederick Merk and Frank Friedel, “Dissent in Three American Wars” (1970).

Of more concern to the readers of this publication, perhaps, is that Stone’s opus does not mention the overwhelming “chilling effects” on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) expressive liberties caused by the Cold War purges of “commie-pinko-queers” from federal and state bureaucracies. For example, an official report issued in 1950 by Republican National Chairman George Gabrielson charged: “Perhaps as dangerous as the actual communists are the sexual perverts who have infiltrated our government in recent years”; by April of that year, 91 homosexuals had been fired from the State Department alone, and others working in the public sector felt at risk.

Nor does Stone address the Defense Department’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy that operates today in our “war against terrorism.” Such “anti-homosexual” measures are directed as much against sex acts as speech acts, of course, and applied as much in peacetime as in wartime; for those reasons alone, Stone might be forgiven any oversight. It is clear, however, that the definitive work on free speech violations inflicted by America’s Kulturkamp against its loyal LGBT citizens has yet to be written.

In the acknowledgements to “Perilous Times,” Prof. Stone recognizes two of his most significant mentors: former University of Chicago Law Prof. Harry Kalven Jr., a celebrated free speech scholar, and Justice William J. Brennan, Jr., one of the Supreme Court’s greatest luminaries in First Amendment law. Stone puts it humbly: “I hope this book would have pleased them.”

Given the monumental achievement of this work and its likely influence on future First Amendment thought, Stone can be confident that they would have been very pleased, indeed. For I suspect that this will be a book with a long and worthy history

David Skover is a professor of constitutional law at Seattle University. He is the co-author (with Ronald Collins) of “The Trials of Lenny Bruce” (2002), “The Death of Discourse” (2nd edition, 2004), and a forthcoming book entitled “Dissent.”