Molestation, murder of a child at the heart of a family drama

How do we find relief from the terrible tragedies life throws at us?

It’s a rhetorical question, and one for which there is no real answer, at least not one that you’ll get me to believe. No matter how many self-help books one reads, no matter how many therapies are available, the only way through is to keep living. But what happens when the tragedy is so monumental that living seems impossible? When one gets frozen in a moment? What then?

This is the subject of the darkly lyrical and moving play, “Frozen,” by Bryony Lavery now receiving a top-notch production at Circle in the Square

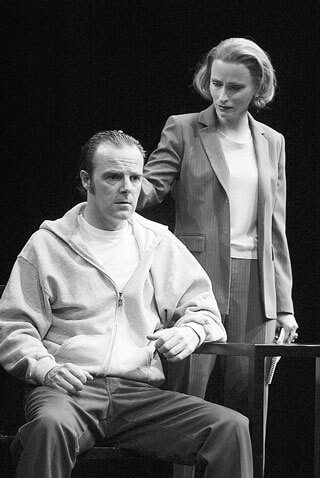

On the surface, the play is about how three characters respond to the molestation and murder of Rhona, a little girl—the little girl’s mother Nancy, a social scientist, Agnetha, writing a paper on serial murders, and the killer himself, Ralph. Nancy, played with absolutely riveting precision by Swoosie Kurtz, has tried to channel her mystification and rage into acting on behalf of missing children. Agnetha, played with great élan by Laila Robbins, tries to keep an academic distance from the events but finds that she is more affected by the other characters than a good clinician should be. And Ralph, the superb Brian F. O’Byrne, is enraged and animalistic, unrepentant and out of reach of any humanity until it is thrust upon him.

Lavery has crafted his play beautifully, layering scene upon scene so delicately that the events pile up for the audience as inescapably as they do for the characters. The playwright makes us feel as if we’ve been crushed by an accumulation of feathers, which is no mean feat. The horror of child molestation is first revealed after Nancy describes a typical sibling battle between her two daughters over make-up immediately before Rhona was abducted, raped, and killed. Agnetha begins her journey screaming into her luggage, before we learn that she is in mourning for her research partner who had recently become her lover. Ralph seems charming until we watch him reenact how he lured Rhona into his van with a soulless amorality and we realize that he kills with the kind of efficiency that most of us bring to the mundane chores of life.

We watch the characters move through their lives, doing what they do, going about their business but unable to unhook themselves from the past. Like the dream Nancy has of a child frozen under a lake whom she cannot reach or save, each character is straining toward some kind of release, but the longing simply simmers under the surface. Nancy cannot get past her anger any more than Agnetha can get past her grief or even Ralph can grow out of his narcissism and psychosis.

It is only when the three lives intersect that their courses are changed, and the real brilliance of the play shows in the small moments that define those changes. It is in Nancy’s considering a visit to Ralph, Ralph’s being touched perhaps for the first time by human emotion, and Agnetha accepting the consequences of her actions that the play finds its spirit. For all the grimness of the subject matter, those moments are uplifting—largely because they feel real, honest and, if not happy, moderately hopeful.

Director Doug Hughes does a marvelous job of keeping a palpable tension constant throughout the play, which gives the experience a quiet but inescapable and vaguely unsettling energy. Though many of the scenes are monologues by the characters, one never loses the sense of the three stories hurtling towards one another.

Kurtz never loses the focus of her character and her determination even in softer moments such as when she goes on a date after she divorces her husband. Robbins never completely masks her grief even as she inhabits Agnetha’s professional demeanor. O’Byrne finally becomes a sympathetic character, despite Ralph’s horrific acts, as the subtext of abuse and abandonment in his own childhood is a constant in the performance.

Hughes keeps all of this at a controlled boil, which is far more moving for its understatement.

This is not a play of grand catharsis, but cumulatively it is deeply moving. There are no huge dramatic moments, but if we’re going to be honest, how many lives are comprised exclusively of such moments? Daily living is prosaic, and therefore there is something far more interesting at stake in “Frozen.” It is the realization that once we see a way out of the darkness, our elemental humanity forces us to choose, even on a pre-conscious level. And we must begin again, living with the consequences of our new choices.