Sheila Callaghan’s new play captures women’s words, but not their passions

Sheila Callaghan’s new play “The Hunger Waltz,” directed by Olivia Honegger, reminded me a lot of bad girl hotel heiress Paris Hilton––empty-headed and unschooled in the subtleties of romance, but a downright knockout.

As disappointing as it is, this lesbian-themed play is nonetheless a welcome sight on a New York stage. Sapphic scripts were regrettably absent from the local theater scene most of last year.

Kudos to the Relentless Theatre Company, a Los Angeles troupe which moved to New York and brought this local premiere with it, and Manhattan Ensemble Theatre for taking a risk on a work that does not, at face value, scream hot ticket.

It’s a shame, however, that a ho-hum dullness hangs over “The Hunger Waltz,” the story of a woman named Gwen who is searching for her sexual and emotional identities over the course of 500 years.

On an amazing set that evolves right before your eyes, events take place in the 18th century’s East Coast, the 20th century’s Midwest, and the 22nd century’s West Coast. Why Callaghan did not pinpoint an exact year in each century––the Midwest scene appears misplaced somewhere in rural Appalachia in the late 1930s––is a nagging question.

Each of the three scenes in the 90-minute show shares a similar story: Gwen (Kittson O’Neill), who is married to Walter (Michael Connors), strikes up a friendship with a woman named Beth (Susan O’Connor), who in turn is toying with the emotions of a flirtatious man named Greg (Brent Popolizio).

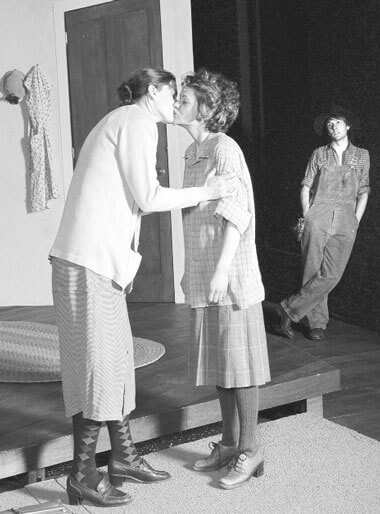

With each scene, the women’s relationship becomes more intimate as the times become more accepting of same-sex relations. The show begins in the 18th century, when Beth is Gwen’s pupil. By the 20th century, the two are bonding over a garden, where they share their first kiss. In the 22nd century, they’ve become full-fledged space age lovers.

To her credit, Callaghan has used an interesting device to explore the trajectory of this romance. On paper, at least, having the two women nurture a romance over the course of hundreds of years is a thoughtful way to explore the timeless themes of love and loss.

But while the show remembers to be romantic, it forgets to be theatrical. Moving from duologue to duologue, from stage right to stage left, the story manages to make Gwen’s awakening a monotonous exercise in death-by-discussion.

Honegger hasn’t figured out what tone she wants to set for Callaghan’s overly-chatty story, rendering the proceedings an unengaging gray shade. If plays about gay men are often obsessively focused on sex and on-stage nudity, Callaghan’s play suffers from too much talk and no heat.

Callaghan also displays a sympathetic, yet curiously regressive view of gender dynamics. The men in the play are either master manipulators or arrogant buffoons who usually manage to woo back their girl, or at least make her feel guilty for seeking fulfillment elsewhere. In the end, the women’s relationship with each other is constantly subsumed by their relationships with their men.

O’Connor is wonderful as the woman whose affections remain elusive. This agile actress brings a breezy naturalness to her characters, finding the right mix of sadness, anger, and vulnerability in each one. Despite a penchant for mugging, Brent Popolizio is earnest and charming as Greg.

Unfortunately, O’Neill and Connors are far too wooden in roles that call for everything from despair to wide-eyed enthusiasm. Their scenes, sexual and otherwise, fail to exude the electricity they require.

This show’s production design is outstanding. Orit Jacoby Carroll’s gorgeously layered triple set-within-a-set is as visually complex as it is resourceful and ingenious. Dana Sterling’s evocative and mysterious lighting is the perfect accent.

Masterful is the word that best describes Naomi Wolff’s costumes. The 18th century period dresses and suits are lush and cinematic. The 22nd century costumes are concocted from a palette of whites. These thoroughly wearable creations—Greg’s skirt and muscle T-shirt bring to mind Helmut Lang––are simply dazzling.

It’s a shame that the talent––both acting and technical––is wasted on a show that’s all dressed up, with too little to say.