Pacific combat veteran outlives his silent service

Bill Horne, a 79-year-old gay veteran of the Second World War, remembers reading about the Navy pilot who went below decks and blew his brains out after learning that he was the subject of an investigation because he was gay.

“Why should gay troops serve openly?” asked Horne. “Because they are people. They have rights under the Constitution. They are Americans.”

On December 23, a CNN/USA Today/Gallup poll indicated that 79 percent of Americans believe that gays and lesbians should be allowed to serve openly in the armed forces.

This past July, the Urban Institute, a non-partisan research group in Washington, D.C., released a survey that estimated that of the nation’s 27.5 million veterans, one million are gay and lesbian, based on a methodology that counts the overall American population as 4 percent gay and lesbian.

The study was based on data gleaned from the 2000 Census that for the first time included information about same-sex relationships. Gary Gates, who compiled the veterans’ research, admitted that the results are not statistically foolproof and do not include an age or term of enlistment analysis. For example, as a percentage of the population, there were certainly many more gays and lesbians in uniform in the “Greatest Generation” during the Second World War, due to mandatory service requirements and the duration of conflict, than there are gays serving in Iraq today. However, America’s gay soldiers must remain closeted while troops of the nation’s two leading allies, Israel and Britain, may serve openly.

In 1943, Horne was a young sailor serving on a Navy destroyer, the U.S.S. Murray, in the South Pacific. The battles in which he served and fought are as immortalized in the American consciousness as Gettysburg or Appomattox, and are emblematic of the nation’s passage into superpower status. Saipan, Tarawa, Truk, Leyte Gulf, Tinian. The names conjure hard-fought contests that left thousands buried on foreign soil, or in the ocean’s deep.

Leaving Louisiana as a 17-year-old boy, Horne’s self-recognition of his sexuality was curtailed by a repressive society’s prohibitions and his own self-hate. He described high school in terms not unusual for many young gay Americans, regardless of era, as a time of bafflement and confusion, a time of growing awareness in his “otherness” and the nearly unceasing desire for physical intimacy with another young man which only shameful fumbling in a backwoods lot infrequently permitted.

The rush to war and its patriotic ostentation following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor seemed like foolishness, said Horne.

“I just thought it was all so silly,” he recalled when news of the attack reached him on the front porch of his home in Oakdale where he and Harry Steed, “the only other gay person he knew at school,” and the boy with whom he first experimented sexually, were listening to the phonograph.

Speaking in a stately manner, Horne often cocked a polite glance when posed with a question he doesn’t understand or would rather not answer. The years of New York living punctuate his Southern gentility as well, in the occasional epithet when his passion compels his speech to flow freely.

“For high school dances I had arranged dates with females, but the boys I wanted to take—oh, well,” he said.

Later, there were college music scholarships offered, but Horne never pursued them.

“I wanted to study music, but was just so full of fear.”

As other young men enlisted in the service, Horne reneged, taking a civilian post at a military installation near home.

“I was afraid of barracks life. Not the sexual thing, but I was terrified of the hazing I heard about. And my brother had joined the Army and just loved it and I wasn’t particularly close to my brother.”

The Japanese conquest of the Philippines dispelled Horne’s private plans to sit out the fighting in some sleepy post.

“I was listening to the radio during the Bataan march and being horrified by it and realizing I had to do something,” Horne said.

By the end of April 1942, the Japanese Imperial Army had conquered the Philippines, then a United States colony. Surrounded, malnourished, and without hope of reinforcements, the combined American and Filipino force on the Bataan peninsula was herded off to prison camps deep in the jungle. Thousands died en route and the news accounts of the maltreatment of prisoners outraged Americans.

Horne enlisted in the Navy.

Standing naked in line for “short-arm inspection,” a doctor’s check of his genitals for hernias or syphilis, was “hor-r-rendous,” said Horne. “I’d never experienced anything like that in my life. I was very ashamed of my body. I had a good build, because I used to run, you see, but never took up games like the other fellows.”

After boot camp in San Diego, Horne went on to radio school and specialized in communications for the length of his enlistment.

The Navy then sent him to Port Arthur, Texas where he boarded what became his home for the next several years—the U.S.S. Murray, a destroyer that carried torpedo tubes, a variety of anti-aircraft machine guns and five 5-inch guns, cannon-like armament that enabled the ship to shell opposing craft or nearby shorelines. In short, Horne found himself on a typical naval workhorse, thousands of which were constructed during the war and deployed mostly in the Pacific.

After a practice run up the East Coast, the Murray sailed through the Panama Canal and entered the Pacific war zone.

More than 61 years later, Horne has difficulty recalling the specifications of the Murray’s guns or the exact order of battle in which the ship fought.

“I could never remember what fleet we were in,” he admitted. Rather, he remembers the people and the feelings, some of which are immediate and still ferocious.

His are the anecdotes of a man who harbored a deep longing to love another man, the absence of which generated an intense pain that perhaps only service in a combat zone could alleviate.

“I was a fast typist in school and so I guess they sent me to radio school and I learned that and so I spent most of my time in the radio shack with the other radio operators. We received the messages in codes and delivered them to the officers,” he said.

Infrequently, detachments of sailors debarked and were ferried ashore after territory under Allied control was made secure. These outings were no cause for revelry.

“Oh sure, I remember the Fuzzy-Wuzzies, the native women, I don’t remember where, who had big puffy hair. Fuzzy-Wuzzies we called them.”

There was scant time or inclination to make any connection with another young sailor.

“There was a very young, very effeminate boy who was actually very popular,” said Horne. “Sure, some made disparaging remarks, but he always had a bunch of guys around him. Maybe it was like prison and he had a bigger guy protecting him, but the thing was I shunned him, just avoided him. I didn’t want to be like that.”

There was work to be done in the radio shack, and the infinite, manifold duties of a sailor aboard a combat ship. The company of one young man did break the tyranny of denial, however.

“He was a ‘striker,’ or a newcomer who didn’t have a stripe,” said Horne, who was a petty officer. “I fell madly in love with Jerry –the nickname we gave him. He worked the same shift in the radio shack and was strikingly handsome. A very nice man, and very macho.”

He was also very straight, said Horne, and while Jerry may not have engaged as readily as the others in the randy sexual braggadocio of young men cooped up in close quarters, Horne knew a relationship with Jerry would never be more than platonic.

“Then there was another fellow, an Italian from Brooklyn. He had a wonderful body, like these body builders today and oh, the hair on his chest. He would come back from the shower and just prance in front of us, toweling off. Absolutely gorgeous,” Horne recalled. “Also absolutely unapproachable. Oh, I don’t know. I am not the kind you should write about for a gay newspaper. I don’t have a great gay history.”

Leaves in San Francisco and Honolulu while the Murray was in dry dock were not occasions for sexual dalliances. Harry Steed, a new beau in tow, met Horne once in San Francisco, banishing any hope of their former backwoods intimacy. Steed shared how two male acquaintances had gotten married.

“I was totally shocked,” Horne said. “Married? Truly, the first time I heard the word homosexual was once when my mother and an older female cousin whispered it about this fellow in town. I ran and looked it up in school.”

Between work, reading books, and an occasional card game, there was warfare.

Horne parried those questions less easily, rising quickly from his chair in his Penn South studio apartment to retrieve old photos and newspaper clippings, shifting the conversation. Then, seated again, leaning forward, his face frozen in a grimace, like he might burst out laughing, emotion poured forth.

Orders came down that a Japanese frigate bearing supplies was to be torpedoed and sunk. Rather than pluck civilian survivors from the sea, the crew would gun them down. Horne recalled the burning bodies leaping into the sea and outreached arms that went ignored.

“It was horrible,” he managed, sobbing, covering his face. “Why don’t they show the pictures of the children in Iraq so they know how horrible it is!”

November, 1943. After three days of carnage, the Marines had managed to secure a beachhead on the tiny atoll of Tarawa, the jagged outcroppings of a mountain submerged beneath the Pacific, where the Japanese had fortified landing strips. The Murray was detailed to retrieve dozens of dead Marines trapped by the offshore reef who were mowed down by Japanese pill boxes.

“There was canvas. We got them out of the water and put them in canvas. Burial at sea and all that,” said Horne.

In three days of combat, 1,000 Marines were slaughtered on the beaches of Tarawa.

“I am so sorry,” Horne said. “I never get like this,” struggling to speak.

The engagements continued. Leyte Gulf was the final push to reclaim the Philippines from the Japanese.

“They sounded GQ, general quarters, and,” Horne said, “it was absolutely crucial to be at your post. We were hit by a Jap air bomb and I went up on deck and the day was night. The flares just lit up the night. Very disorienting.”

Hundreds of salvos later, the crippled Japanese fleet sailed north.

“Any battle I was in was easier than those battle exercises––which I simply detested,” said Horne.

One August morning in 1945, somewhere off the coast of Japan, the crew was informed that the loud sounds the night before came from the Enola Gay as on its way to Hirsohima.

“We didn’t see any of that. I was glad it was over. Some people came home with Japanese helmets––and this is horrible––but some of them they would scrape the remnant of skulls out of the helmets.”

By 1952 after completing college on the G.I. Bill, Horne was in New York City. Spending a night in the Chelsea Hotel, he looked down from his terrace.

“There were these five gay fellows in a convertibles and they called up to me and I thought, ‘Oh, my,’” he said in recollection of what was for him the signal moment of his self-recognition.

Nevertheless, he married a woman.

“My wife, Esther, was a real leftie. I told her I was gay and then we never talked about it again.”

Horne became a public school teacher and fathered two children, one of whom died in infancy.

“My son had a drug problem and I was in one of the sessions with one of his counselors, a very intelligent Puerto Rican guy. He asked me one day, ‘Well, Bill when are going to come out?’”

Horne retired from the school system after 20 years. He had had no sexual contact with another man during his marriage.

“I told Esther something like, ‘I’m still gay,’ and she acted shocked. I could have stayed married, I supposed, but I knew there was something else for me, that being married was something else that other men did not do.”

Horne divorced and moved into an apartment in Queens. While he spent time with gay acquaintances, he never fostered a committed relationship with another man. He fixed pianos for money, a second-career that allowed him to indulge in his love of music. The isolation led to loneliness. He began to drink heavily. Life dragged on.

At the age of 75, Horne stopped drinking and got sober with the help of a 12-step program.

He began to play the piano again. One day he showed up at a meeting of the New York chapter of American Veterans for Equal Rights (AVERNY), an LGBT veterans group.

“He bloody well served through every campaign in the Pacific,” said Denny Meyer, AVERNY’s president. “He came in off the street one day with all these medals and was out and proud and he can camp it up too, which is nice.”

Meyer added, “Bill’s generation went through an entire different thing. These men who came from small towns, they didn’t know gay people existed.”

Horne serves as AVERNY’s vice president. As such he has taken an adamant stand against Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell and has called for its immediate annulment.

“If out troops are accepted by their peers, then there will be no effect on morale. It has to come from the commanders,” he said.

An outspoken opponent of the war in Iraq, Horne supports the presidential campaign of Dennis Kucinich, the Ohio Democrat, who advocates a unilateral withdrawal of American troops from Iraq, but fearing his candidate is not electable, Horne will cast his vote for former Gov. Howard Dean, another anti-war Democrat, “although he’s not my favorite.”

Horne insisted that Pres. Bush allow the press to film the troops who have been mutilated in the Iraqi war as a means of educating the American public about the horrors of combat.

“After Word War I, my parents spoke of how the damaged men were left hidden in war hospitals. The same is happening today.”

He denounced the rationale for invading Iraq.

“Pearl Harbor was a sneak attack by another government. 9-11 was not done by a nation, but by a terrorist group, supported by one of our allies—Saudi Arabia.”

The only reason the U.S. maintains ties with Saudi Arabia, contended Horne, was because “the Saudis are friends of the Bush family.”

After being sober five years, Horne, 79, said, “I now feel like I am really, finally living.”

Recently, after a Veterans’ Day event, he met a fellow veteran, “ a boy really, just in his 60s,” and the two have spent time together. “It’s not the idea of having sex,” said Horne. “It was just more the idea,” and he paused, “of being held.”

Horne quoted Gertrude Stein.

“Until a person becomes who he is, he’s not complete,” he said. “That’s the story of my life.”

Then and Now

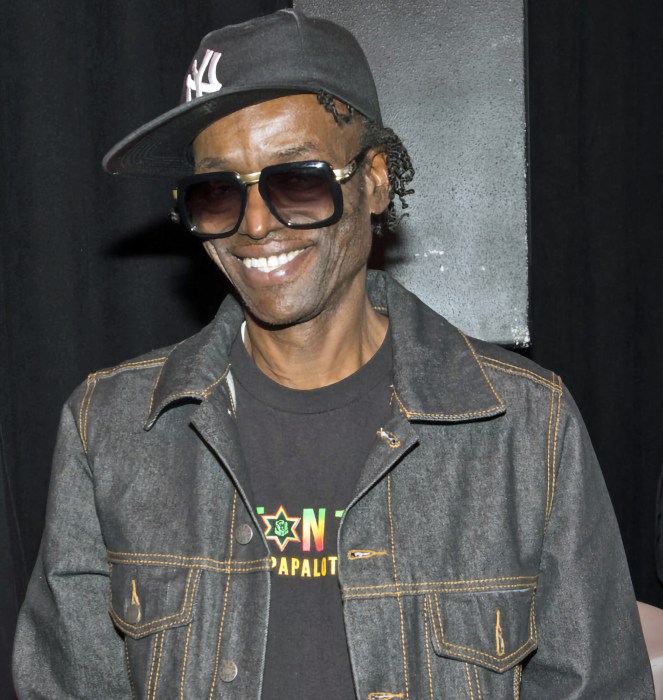

Bill Horne (first above) on leave with a fellow U.S.S. Murray shipmate; Horne in a recent photo at his New York City apartment.

We also publish: