Reissued photo book and museum exhibition mark Tribeca’s emergence

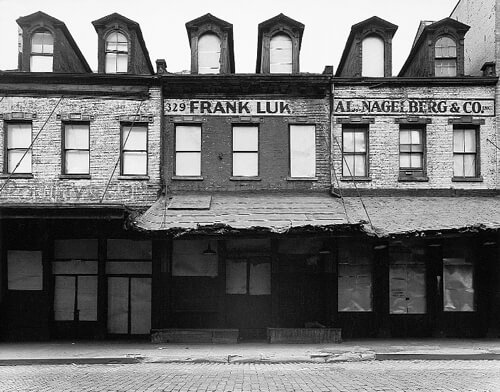

“327, 329, and 331 Washington Street, between Jay and Harrison Streets,” though drastically different in look today, were among the few buildings slated for demolition in the mid-‘60s clearing of Lower Manhattan that survive to this day.

The pages in a staggering new book called “The Destruction of Lower Manhattan” are not numbered, but the photos are. Halfway through it the first time around, I was stopped in my tracks by photograph No. 34, not of some building now as extinct as the mastodons, but simply: “Woman in a phone booth.”

This is in fact an old book reborn. Reissued now. Every one of these 83 photographs taken 38 years ago by Danny Lyon—street after street, building after building after building of a moonscape sledge-hammered into dust—would carry the dream force of a painting by Giorgio de Chirico, but the casual No. 34, with its double reflection bounced off glass, had, for me, jolting affinity to a photo of a very different woman on a different, earlier sidewalk by a deity of sorts named Walker Evans (1903-1975), who, among much else, took the New Deal-era portraits of Southern sharecroppers that went with James Agee’s text in “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

Evans is not just my deity. In a long section of text by Lyon at the end of ‘The Destruction of Lower Manhattan”—an epilogue recreating the history of these flash-frozen shots of the 1966-67 demolition of 60 acres of Lower Manhattan in cross-current with Lyon’s own life in those times—one suddenly comes upon the following:

“The truth was that [there in 1967] I was somewhat conflicted and partly ashamed of the work. I thought it was completely unoriginal. Worse, I had been paid to do it … I also thought the whole thing was inordinately influenced by the work of Walker Evans, who was perhaps highest in my pantheon of great photographers.”

Unoriginal! Never lose the courage of your tintype, Lyon. The photographs are about as unoriginal—these images of naked, dying streets and structures, taken on empty, early Sunday mornings—as the invention of the alphabet, or the wheel.

Go up to the Museum of the City of New York, where the work is on exhibit through September 18, or beg, borrow, steal the book, and see if you don’t agree with me.

I was working at the New York Post back then, the old Dorothy Schiff New York Post, at 75 West Street, a few blocks south of where Radio Row, the Washington Market and everything else was coming down—being smashed down—for the hulking towers that would one day be smashed down themselves in a way that nobody could have foreseen in a million years. September 11, 2001, is of course inherent in Lyon’s new old book, but it is never stated.

We ink-stained wretches at 75 West Street used to walk out, sometimes, at lunchtime to see how the destruction was developing, and to commiserate over the old bars and eating places and gadgetry shops and other curiosa that were day by day ever more gone with the wind.

Lyon’s images, captured by clumsy, old-fashioned tripod-supported view camera—the image itself first coming into the photographer’s view upside-down on a field of ground glass—are just about all that remains of that particular quadrant of the world, or of the equally flattened area to the east around the Manhattan end of the Brooklyn Bridge. Gathered together between covers, Lyon’s relics compose an archaeology as evocative, as lost and gone as Nineveh and Tyre.

Edward Hopper once said, “All I ever wanted to do was paint sunlight on a wall.”

Take a look at, for instance, Lyon’s photo No. 26: “The south side of Jay Street at West and Caroline Streets.” If that isn’t Hopper’s sunlight on a wall—sunlight and shadow, with the sightless eyes of blackened windows marching along the same wall—well, it quite simply is. Standing sentinel in the foreground, giving frame and depth to the Hopper in the near distance, is one lone goose-necked lamppost with its one lonely “Caroline” street sign.

Danny Lyon, born in Brooklyn in 1942, raised in Queens, had a full life before and a full life after the “Destruction of Lower Manhattan” project—much of which, he confided in some detail, was shot while he was high on peyote and other ephemera. He had spent a couple of years earlier as a member of SNICC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, participating in and chronicling the civil-rights upheaval of the first half of the 1960s; then a couple of years riding a cycle with the Chicago Outlaws—both of which experiences produced important books, though that wasn’t Lyon’s intention in the beginning.

He is always on the side of the underdog, in these and other books and in a number of well-regarded documentary films. He has had many exhibits all over the place. “The Destruction of Lower Manhattan” was originally published by Macmillan in 1969 and, we are told, was remaindered a few years later at $1 a copy. The powerHouse reissue, at 160 pages with 83 photographs, is $50.

Lyon resists talking about this work any longer. No interviews. It’s all, he feels, in the photos on those pages, or on the walls of the Museum of the City of New York.

“I came to see the buildings as fossils of a time past,” he wrote in his original introduction. “These buildings were used during the Civil War. The men were all dead, but the buildings were still here, left behind as the city grew around them. Skyscrapers emerged from the rock of Manhattan like mountains growing out from the earth. And here and there near their base, caught between them on their old narrow streets, were the houses of the dead, the new buildings of their own time awaiting demolition. In their last days and months they were kept company by bums and pigeons.”

And by Danny Lyon, with camera.

gaycitynews.com